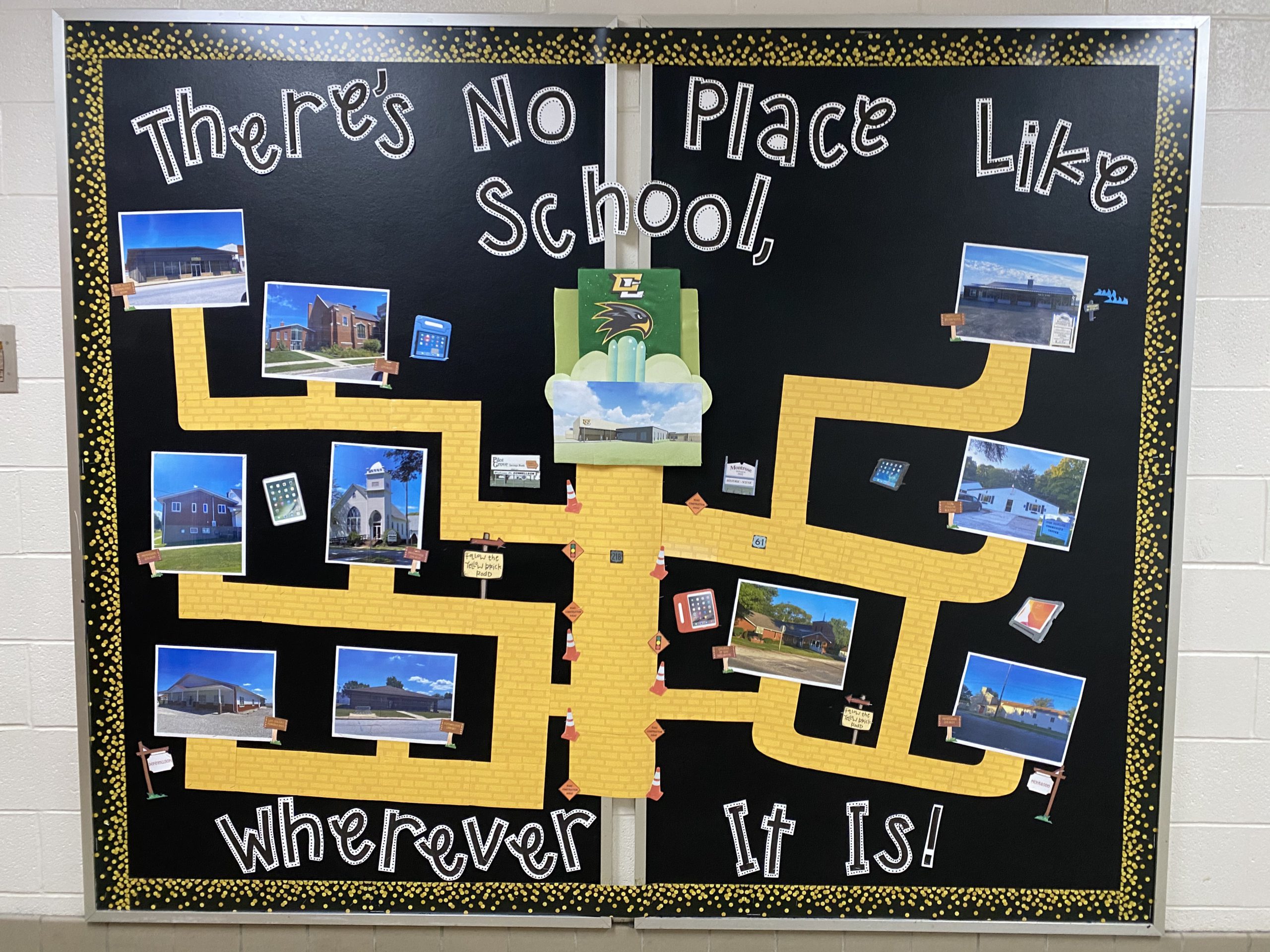

Conversations about the concept of relocating some classrooms to buildings throughout the community never really got off the ground in most school systems. But as the idea came up and got dismissed elsewhere, officials at Central Lee Community School District were out visiting churches, community centers and other local facilities “making the sell,” says Andy Crozier, superintendent of the 1,200-student rural district encompassing three towns as well as several hundred students from elsewhere since it’s an open enrollment district. In late August, all Central Lee students in grades 3 to 6 began the school year in a total of 15 offsite “PODs” in Donnellson and Montrose, allowing grades K-2 at the elementary school and 7-8 at the middle school to more easily socially distance.

Planning began with “hours of discussion” in May and June about how kids could get back to school safely, says Crozier. The team began targeting the elementary level, where being fully remote would be most problematic for students and families. With social distancing measures, 20 kids in a classroom would not be feasible at the school. “We knew we had a variety of community spaces two to three times the size of our classrooms. We were just trying to minimize interaction as much as possible.”

Perhaps a few classrooms could be moved off-site, reducing crowds in hallways, restrooms and the cafeteria? “That idea blossomed to every classroom, third through sixth grade,” he says. This would take third, fourth and fifth out of the elementary school as well as sixth out of the middle school.

The administration team brainstormed a huge list of any possible space in the community and divided it up. “We all went out and talked to people in those spaces about our idea and possibility of using the space,” he says, adding that the site visits were a chance to identify the truly usable spaces. This involved class size flexibility. Some larger PODS can fit a few additional kids (such as 24 rather than the typical 20), and one space only has room for a class of 18.

“We kept it under wraps as much as we could,” Crozier explains. “We didn’t want to freak our parents out. By the time we had our sixth or seventh discussion, word was getting out. But by that time we had formalized the plan.”

In mid-July, a letter and video message from Crozier went out to families, sharing why the POD system was necessary for opening up in-person instruction right now. Parents learned that physical education, music, art, lunch and recess would still be available to students placed in pods—and that parents could choose an online-only school option if they preferred.

Here’s how Crozier—also the parent of two students attending class in two different offsite locations—and his team handled various areas of POD system planning and execution.

– Parent concerns:

“We had a lot of questions early on, since this is such a foreign concept for parents,” says Crozier, adding that overall they were very happy their kids would be able to attend school every day. Administrators worked to based POD locations on geographic location, with students living in Donnellson being assigned a POD in that town and those living in Montrose getting a location there. An FAQ page answered questions about transportation, meals, safety and security.

– Teacher concerns:

“We could tell right away that they were not in favor of it to begin with,” shares Crozier. “It took a lot of convincing them about why this was a good idea.” Communication started with a Zoom conversation for all elementary teachers, and then teachers by grade and eventually individual teachers. Sixth-grade teachers had the most upheaval, because they went from teaching single academic subjects at the middle school level to teaching all subjects again. “They had to quickly ramp up their skills,” he says.

Crozier and his team tried to listen to all teachers’ ideas and incorporate their input. “At the end of the day,” he says, “we had to tell at least a couple of them, ‘This is just what we’re doing; we know you’re not super comfortable with this but this is what is going to keep you and your students the most safe.’”

A month into the POD system, he adds, “our teachers were loving it. They said, ‘I don’t want to move; I feel safe here.’ We call it ‘living the pod life.’”

In most cases, students whose families chose full-time distance learning were placed with a fully online class and teacher. Fourth grade has a whole distance learning class and grades 1 and 2 have a combined class. In just a few cases, teachers are having to simultaneously teach children in the POD and at home.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”A month into the POD system, “our teachers were loving it. We call it ‘living the pod life.’” —Andy Crozier, superintendent of @CentralLeeCSD in Iowa, which opened 15 offsite classrooms this school year” quote=”A month into the POD system, “our teachers were loving it. We call it ‘living the pod life.’” —Andy Crozier, superintendent of @CentralLeeCSD in Iowa, which opened 15 offsite classrooms this school year”]

– Space use negotiation:

District officials negotiated a contract with each outside organization for use of the space, with many of the contracts mirroring each other. “We did it in three weeks. It was a mad rush from mid-July to early August,” says Crozier. “Our attorneys helped us out considerably. And really our partners weren’t asking for the moon.” The Donnellson Public Library, for example, requested that when kids entered through the main part of the library they would use hand sanitizer, just as any patron must. “It was little things like that, and we took care of them all,” he says.

Some facility owners are charging a nominal rental fee and others are donating the space. Still others just want to be paid for utilities used. The agreement covers liability and who is responsible for reporting COVID case instances. A few POD locations have had plumbing issues and the district maintenance team took care of them “even though we weren’t contractually responsible,” says Crozier. “Ultimately we want to leave these places in a better condition than we encountered them.”

– Security and supervision:

Many of the locations have a single classroom, which could leave teachers and students feeling vulnerable. Each partner agreement addresses security in some way. For example, in the church PODs, no church patrons are allowed in the buildings between 8 a.m. and 4 p.m., and the doors are always locked, with a sign saying no one can enter. All sites have either limited or no access to the public.

Donnellson and Montrose PODs each have a staff member assigned as POD leader, responsible for being nearby at all times and dropping in at least once a day. “We needed people with strong communication skills who are highly organized to take on those roles,” says Crozier.

Parents contact the POD leader if, for example, their child needs to be picked up early due to a doctor’s appointment.

In addition, local police monitor the POD areas.

“As a parent, I could not feel safer,” says Crozier, adding that being able to mention his children in PODs has given him “considerable credibility.”

– Recess and specials:

In scoping out potential POD locations, administrators looked for those with green space on-site or a city park within two blocks that classes could walk to. The district supplied some balls, bats and other equipment at each location. Music, phys ed, band and art teachers will visit the PODs for specials.

– Special education supports:

Some PODs have a special education teacher, and others have shared special education teachers and associates who travel from site to site. “We’ve paid a lot more in teacher mileage this year than in the past,” Crozier notes.

– Connectivity:

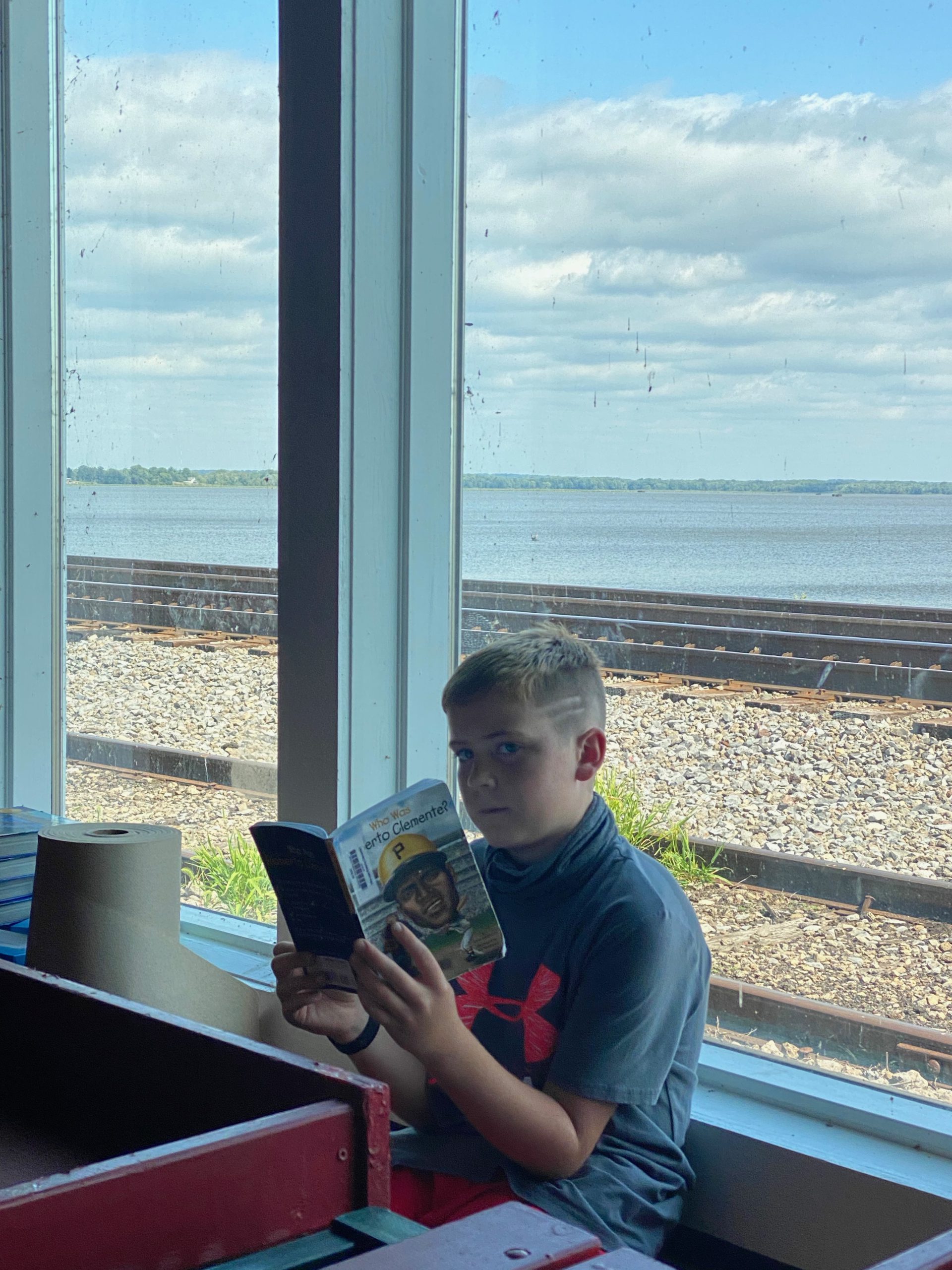

The district technology director utilizes hotspots, DSL connections and any other solutions he could to get WiFI connectivity to each POD location. “The first two weeks were a little rocky,” says Crozier. “But now it’s OK.”

Every student in the district has an iPad for use, although each of the grades already had 1:1 devices prior to the pandemic.

– Meals:

The district’s nutrition director figured out all the logistics of supplying breakfast (grab-and-go) and lunch (available by individual request) to the POD classrooms. “Kids are getting the actual lunches served in school,” says Crozier. The administrative team has a rotating schedule, with each member taking turns delivering lunches by van via a single route. That team includes Crozier, who will never forget the 90-degree day when his first delivery time came up.

– Transportation:

Central Lee maintained transportation availability for all students by setting up a shuttle bus system. Some students ride the regular bus to school and then hop on one of five shuttles to get to their POD. Some students in both Donnellson and Montrose walk or ride their bikes to school each day, and families were encouraged to explore alternative transportation to busing since social distancing could not be maintained on buses.

Countdown to the new school year

When asked about the most stressful time in the planning or execution of offsite POD classrooms for his school district, Superintendent Andy Crozier pinpoints a time in early August when the district was about two weeks away from starting school. “I remember almost having a panic attack after everything was launched and communicated,” he says. “I thought, I don’t know if we’re going to pull this off.” Transportation and lunch logistics had not been finalized, and they hadn’t yet figured out how to get teacher supplies to the various PODS. “WiFi connectivity also gave me a lot of anxiety,” he says.

But the team got the punch list done, with all the PODS opening on time and ready for learning.

In Crozier’s weekly meetings with area superintendents, he knows of a few others who have dabbled in offsite classrooms. “But no one has done it to the scale that we have,” he says. “We’ve had a lot of questions, but when I start talking about all the details some district leaders don’t necessarily want to put in that effort, or feel like they need to.”

– POD phase-out:

Some of the POD classes got phased back into the school building in October and November, but then with the COVID case surge they were phased back. Not wanting to make teacher and students “hop back and forth,” Crozier says, his team decided to announce that all PODs would remain open until at least March 1.

– Costs:

Equipping and operating the PODs did cost Central Lee some extra, but Cozier says the district was able to take on a bit of financial risk because it’s in a good position. About $90 per student was saved from the spring shutdown, in areas such as substitute teachers, professional development and utilities. “In the end it’ll probably be a wash over the two school years,” he says.

To other districts that may want to consider offsite classrooms for the second half of the school year, Crozier says it’s certainly workable. “Where there’s a will, there’s a way—if people want to do it and want to invest the time and energy to make it happen. They can call us and we can tell them the good and the bad.”

And it’s not just rural districts that can execute such a plan. In fact, with urban and suburban areas having more churches and other facilities, he says it may be easier to find suitable locations. He suggests starting with a single grade at a time if a bigger plan is overwhelming.

“As we go through surges that are crippling to our communities, closing schools is also crippling to our children,” Crozier says. “Sometimes you have to spend a little extra money to open up.”

Melissa Ezarik is senior managing editor of DA.