Georgia growers proudly claim their soil is the best in the world. That nutrient-laden dirt combines with a temperate climate to serve up a bounty of high-quality fresh fruits and vegetable year-round.

But even in this state brimming with agricultural riches, there are a few areas where that last mile gets closed off. They are the food deserts, where disadvantaged citizens lack access to affordable, high-quality food.

One of them is Albany. This city of 75,000 is encircled by pecan farms, yet very few of the residents work in agriculture. Part of a region known as the Black Belt, its families instead work in a variety of other industries, with many struggling to make ends meet. Nearly 35% hover below the poverty line. It has faced additional challenges during the past few months, becoming one of the nation’s hot spots for COVID-19 infections and deaths.

The disconnect between the growing community and the people who live near those farms has created a gap in opportunities, especially for younger generations of students who often must leave the area to find that road to success.

However, a program called GroupUP happening within the Dougherty County School System was developed to change that. Instructors and students at the Commodore Conyers College and Career Academy (4C, for short) have been collaborating on a project that not only delivers food to their community but also offers several pathways for them to break into the agriculture industry.

Students from different career tracks – agriculture, construction, marketing and others – have built their own working farm. They designed and built 40 raised-bed garden boxes. They fully irrigated them and put in soil sensors. They created two quarter-acre plots on school grounds where they have composting, honeybees and a plethora of produce.

According to the Academy’s CEO Chris Hatcher, they’ve grown and delivered more than 2,000 pounds of produce into the community during the pandemic thanks to help from partners in the business community and local colleges.

“It really has been awesome and we’re kind of just getting started,” he says. “I can tell you, my kids have never done anything like this.”

Getting the kids on board

The 4C Academy, designed to solve community-wide problems through the collaboration of its 14 different pathways of students, has forged some innovative initiatives since Hatcher (a local businessman who went through the Dougherty County system) took the reins four years ago.

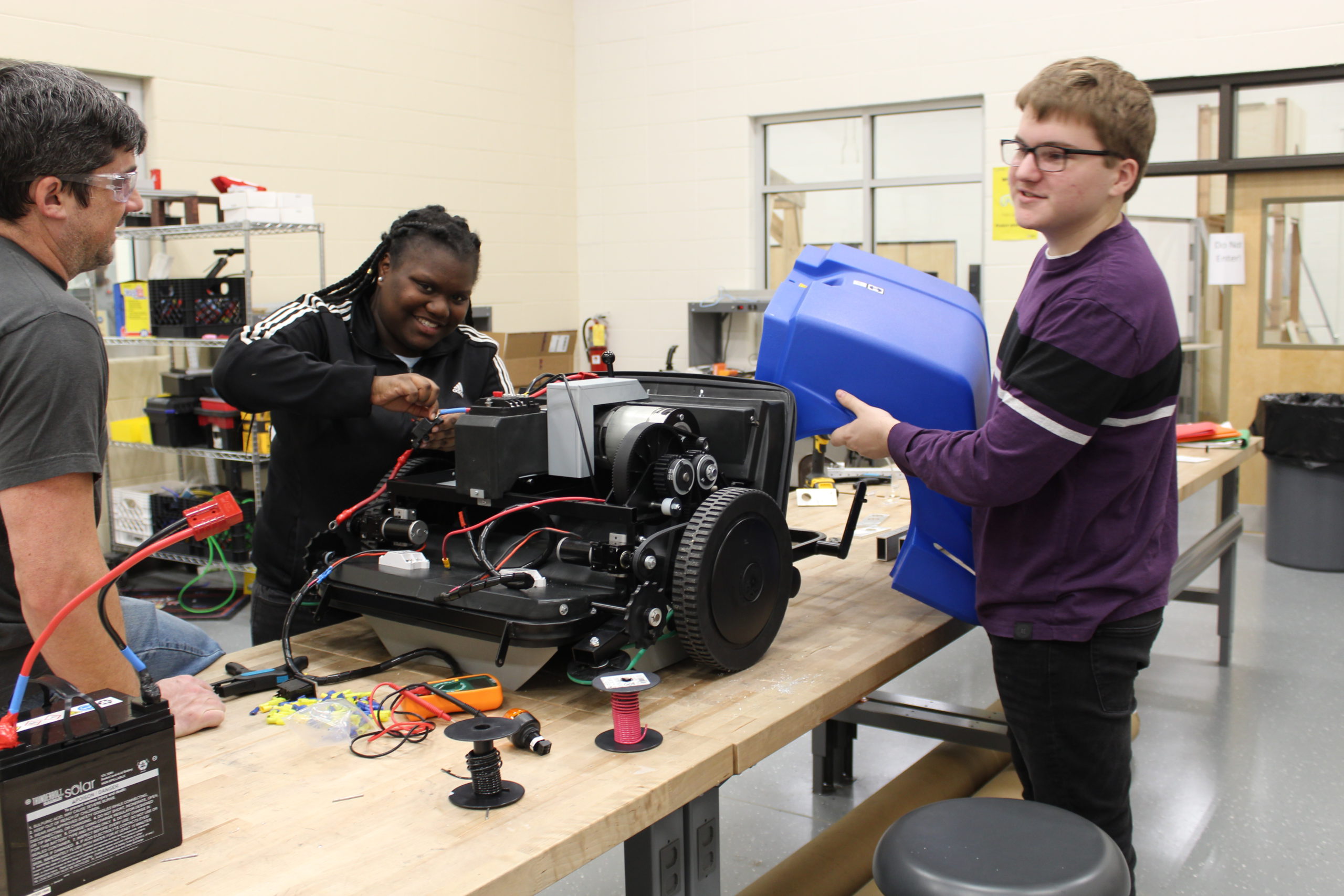

Its robotics students developed a Roomba-style device that collected trash from parking lots. Its renewable energy group developed a “sun bar” to charge mobile devices. Its healthcare group created a healthy lifestyles plan that it delivered to elementary schools.

But making the connection to food might be its most ambitious project. Though agriculture is part of the Georgia lifestyle for millions, it wasn’t a natural fit for these inner-city students, who had virtually no connection to produce and whose families are often cut off from it – more than 80% are economically disadvantaged.

“There was a grocery store about seven years ago that shut down and when they did, the access to our neighbors here in this area, to fresh produce, just dropped off,” Hatcher says. “So, in honing in on a problem they wanted to solve, we came onto this food insecurity piece.”

Beyond that was an even greater challenge – how to sell a project like this to a group of young students.

“What I learned about this generation is they have an attention span of eight seconds, which is down from 12, which was the generation above them,” Hatcher notes. “So, eight seconds, they’re incredibly impatient. They’re used to getting everything on demand, from movies to music to anything from Amazon. They problem-solve with Google. A 50-minute lecture to this group is torture. So when you’ve got this directive from the business community, and you’ve got the realities of the generation over here, we started trying to figure out how we could have the most impact.”

Over the course of two years, they developed a plan based around Fridays at the Academy, which can essentially serve as classroom-free project days as long as it contains STEM-based activities and academic components. To get students on board with the academic piece, they developed “gamified” strategies for competition, including “crop clashes” for students to earn points from various projects.

Hatcher and his team were able to secure a plot of land – converting a former football field, about 5 acres worth behind the school – and pulled together the various pathways to create a structure for growth. They got guidance on growing from a number of ag leaders, most notably Flint River Fresh executive director Fredando “Fredo” Jackson, who has helped bring this project and many others across the state of Georgia to life. Its Small Farmers Distribution Network, in fact, has helped supply six school districts and 40,000 students with fresh produce – more than half a million meals in total each year.

“We learned a lot from our business community – problem-solving skills, critical-thinking skills, communication skills, work ethic skills, a lot of the soft skills,” Hatcher says. “We had three goals: we wanted to show them all about our state’s No. 1 industry. From a career standpoint, we wanted to show them how to grow and prepare fresh food. And we wanted to have every one of our projects have community impact.”

The impact on students, community

And oh how they’re growing and serving. Even though the pandemic has forced consolidation of some areas, the students have been producing a variety of fruits and vegetables on their mini farm. They even built a mobile produce stand, complete with solar panels, to deliver their fresh goods to those in need.

“In our fall crops, we’ve got hearty stuff like collards and mustard greens and carrots, potatoes. This summer, we’ve grown squash, zucchini, watermelon, okra, sweet corn,” Hatcher says. “Strawberries have been a big hit. We went to the food bank and a couple of our distributors of food to get it to those who need it. We said, ‘what would you like to see more of and less of’, so we’re sharpening our pencils to focus on what they want.”

That’s not the only project in the works. Phase II of the GroupUP plan calls for the onsite development of a commercial-scale hydroponics operation that will use robots and drone technology, guided by partnerships with Georgia Tech, Albany State and Fort Valley State universities.

“We’re going to have four different robots in our garden area,” Hatcher says. “Our IT guys are highly motivated about this ag project because now they’re going to be building a robot, a rover that will go between these crops, identifying weeds. Same thing with logistics. It’s one thing to learn about things in a textbook. But when you’ve got a time and a schedule, and you’ve got things that are going to be ready and you’ve got to figure out how to make it happen, it’s got some relevance to it.”

That’s true for many of the students involved from all the different pathways. Hatcher says the convergence of three components of the program – workforce development, a wave of new growing technologies and serving the local community – have synthesized to provide priceless future benefits for students.

“They’re motivated by causes,” Hatcher says. “Part of our objective here is to find what’s motivating these young people to learn. If they can get behind something and see an impact, it really offers a different level of reward for students.”

Others schools or districts looking to replicate the 4C Academy approach need to be open to banking the time and getting the resources to turn this type of project into a reality. Being a part of a charter school system afforded Hatcher and his team the luxury to create a one-day window of time each week to make it happen.

“You have to have partners, that charter system approach or structure and having leadership at the district level that’s willing to try something a little different,” Hatcher says. “Quite frankly, our instructors, this isn’t the way they’re accustomed to doing things, either. We had some friction. I come from the business community and that’s just part of your world. But we got through that and now I think a lot of instructors really appreciate the structure.

“There are a lot of academics embedded in this project. The students are learning math. They’re learning science without even knowing it.”

Chris Burt is a reporter and editor for District Administration. He can be reached at [email protected]