In late September, the 52 schools in Henry County, Georgia, just south of Atlanta reopened for in-person instruction, a pivotal moment for this district whose students had gone six months without being in front of their teachers.

Not all of them returned – only 41% are physically at schools – but being able to bring them back at all showed the power of clear decision-making, collaboration across departments and shrewd planning.

For Superintendent Mary Elizabeth Davis and her team, the everyday meetings with staff at 8:30 a.m. paid off. The brainstorming sessions ended up shaping how those schools would look – from details around COVID-19 protocols to actual instruction.

The one thing that continues to evolve, however, is staffing. A challenge in most districts in 2020, covering key positions throughout a district from teachers to administration is a constant concern. As recently as two weeks ago in the 43,000-student Henry County district, 46 staff members were under quarantine because of their association with someone who contracted coronavirus.

Though the district has permanent subs to cover positions at every school, Davis foresees the potential in the future for gaps in coverage. It’s why Henry County is in the process of forging an Emergency Staffing Action Plan to help take care of those spots, especially in the classroom.

“The substitute limitations are real and we’re realizing them,” Davis says. “We really have to think that every job in the organization is a teacher first. And we may need to call upon you to do that.”

Assessing school needs

From those 8:30 meetings developed a series of ideas on how to cover positions during the crisis. Through July and August, there were considerations that many other districts were thinking about – should they get more permanent subs for schools or could paraprofessionals cover for teachers who were at home?

At Henry County schools, there are currently two permanent subs serving each school. Each day they identify the needs in those schools – from paraprofessionals to certified administrators – and then fill in gaps as needed. However, those holes have become more frequent since the start of the pandemic.

“What we’re finding is those needs aren’t short term,” said Dr. Anissa Johnson, executive director of human resources. “Quarantines are 10 days or 14 days, and they’re overlapping. We’re having to provide critical coverage and meet staffing for those areas for those days when they do extend beyond 10 days, and they overlap.”

The solution they came up with is far more robust than previous models. In looking at all of its roles – from front office to clerical – the team talked about how they could still run at full capacity if there were absences. It was determined that those who had experience within the district could function in other roles if needed.

“We’ve got a lot of district-based people who have prior professional experience in a principalship, or school administration,” Davis says. “We’ve got prior experience in teaching or other support professions that are credentialed. And then we also have people who don’t currently work in schools who have prior experience working the backbone of a front office or cafeteria as clerks or secretaries. We essentially took every employee who’s not assigned to a school, and we’ve created an emergency action staffing team.”

For example, Davis says, a former principal might be assigned to the principal staffing team.

“So, if we’re going to have a principal out two weeks for quarantine, then how do we not even think twice about a former principal who might be an assistant superintendent going to serve the school as the principal? The same is true for every job.”

The advantage of this approach Davis says is that “schools feel like the district approach to support isn’t just to tell you what to do, it is actually to come and do alongside you as necessary.”

Putting it in place

In order to make the Emergency Staffing Action Plan a reality – it is still on the launch pad for now – it entailed collecting names and roles of every staff member in the district and included former work they performed.

From there, the team could determine what positions and locations those people could serve. Beyond filling teacher roles as necessary, they considered clerical workers as well because they can just as easily affect how schools function. From there, communications strategies were developed around the plan.

“Once we’re ready to launch this, once we’ve identified a school that needs support, we will have an email ready, and we’ll have a sub team ready to go,” Johnson says. “We’ll say, XYZ school, you will receive these individuals to step in and support you. These individuals will already have received their email, saying tomorrow, you will serve XYZ school in this capacity and you’re expected to report at this time. This will be your role. You will be needed for two days to fill in until we get this vacancy supported.”

Added Katie Truitt, assistant superintendent for instruction and learning, says for teachers, the transition is going to be seamless.

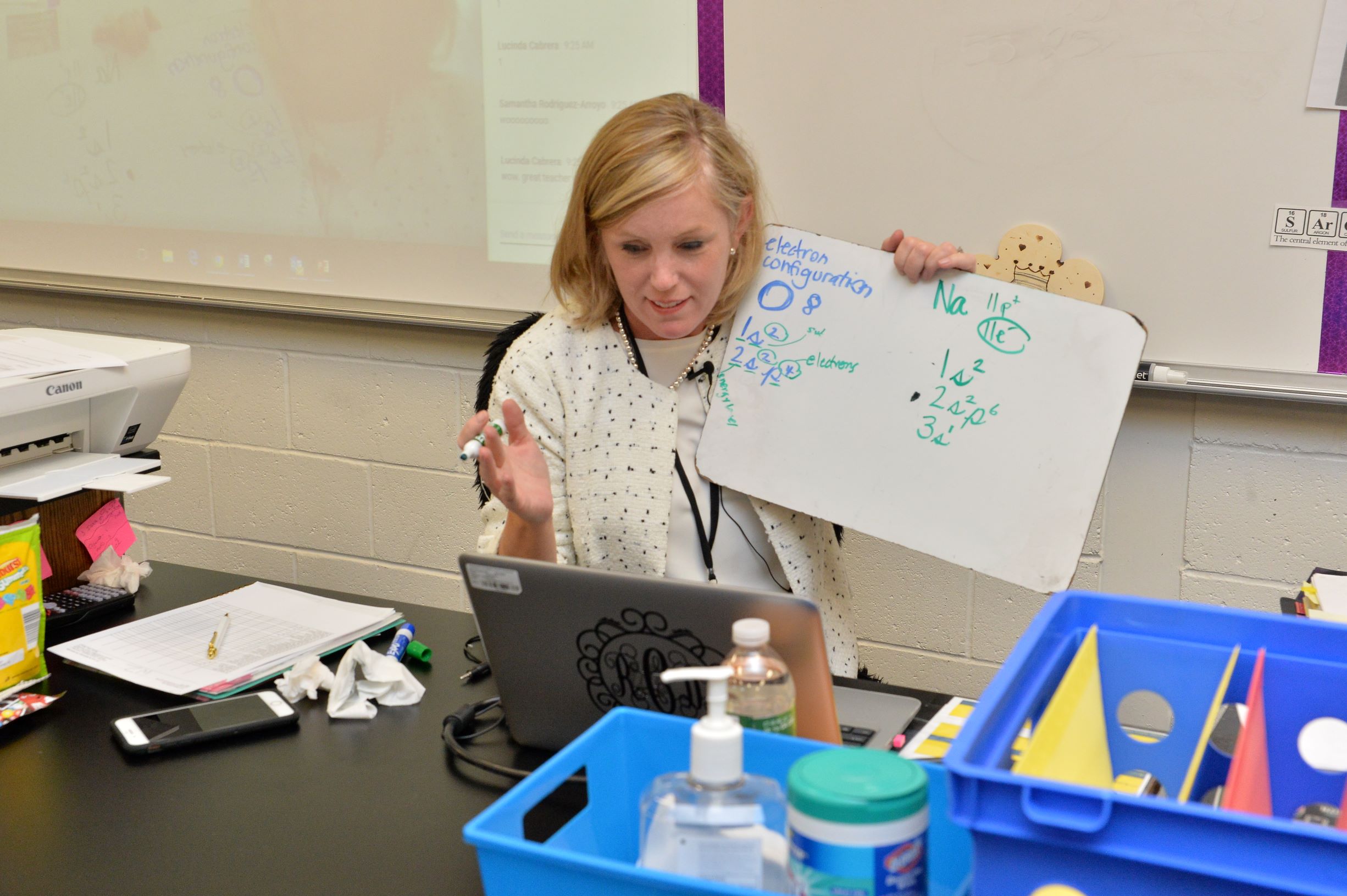

“They’re going to see somebody come in the building and take over a classroom,” she says. “They may recognize that person from other work that they’ve done or they might not. The goal is to make sure that students are receiving quality instruction. So, if the teacher is able, then that teacher will continue remotely and if the teacher for whatever reason is not able, then you have someone who is a state-certified person sitting in that seat to help bridge that gap.”

How to make it a reality?

Formulating and ultimately executing a plan like this, Truitt says, starts with perspective and a can-do attitude.

“What’s the most important thing that we do? We teach students. That’s our core focus,” says Truitt. “When we started talking about potentially coming back face to face with all of our teams if we’re needed, that’s where we’re going. All of us have been asked to fill in roles and to do things that are sometimes outside of their portfolio of work.

“If you have a core vision of what the most important things are, it’s really easy to communicate that. If the understanding across your entire district is that we need to work together to solve problems, then it’s not shocking to teams to be asked to step up in ways that they don’t normally work.”

Truitt says other districts can model the same approach – bringing various stakeholders to the table as Henry County did with human resources, instruction and leadership – but they must be willing to change just as school-based employees have had to frequently adjust.

“Developing that ability to bring people to the table that don’t feel like they might naturally fit is something that you have to ingrain in your culture,” Truitt says. “I won’t say that’s an easy process. It can be a little tricky. But looking at who needs to be at the table to think through things is important on the front side.

“Then thinking ahead. As Mary Elizabeth said, we weren’t thinking about it in July, but we definitely were thinking about it long before we’ve ever needed to act on it. That’s the key: trying to look at what are we solving now and what potentially could this cascade into problems if we don’t get out in front of things. If we see trends going a certain way, then where do we need more communication? Who do we need to communicate with? Having people looking at an issue from all sides through their lens really brings powerful solutions.”