After AI, the science of reading may be the hottest topic in education as 2024 gets underway. The most important way to strengthen and spread this research-backed practice is for school leaders to help teachers develop their literacy skills, a new report contends.

Five policies must be in place for that to happen—particularly in the early grades, the National Council on Teacher Quality’s just-released “State of the States” report asserts.

“States that have seen elementary students’ literacy rates increase have done so with a long-term commitment to improving teacher effectiveness,” the report notes. “They not only changed reading instruction by bolstering teachers’ knowledge and skills through initial adoption of strong, aligned, coherent policies, but they coupled these policies with ongoing support and financial resources.”

More from DA: Want students to be more engaged? Don’t ban cellphones!

Over the last 10 years, some 32 states have enacted new laws or policies around evidence-based reading but even more needs to be done, the report contends.

Starting with state decision-makers, five things have to happen to ramp up the science of reading. K12 leaders can lobby for some of the policies while others may become the subject of state mandates:

- Detailed reading standards for teacher prep programs.

- A review of teacher prep programs to ensure they teach the science of reading.

- Adoption of a strong elementary reading licensure test.

- Requirements for districts to select a high-quality reading curriculum.

- Providing professional learning for teachers and ongoing support to sustain the implementation of the science of reading.

Science of reading in your state

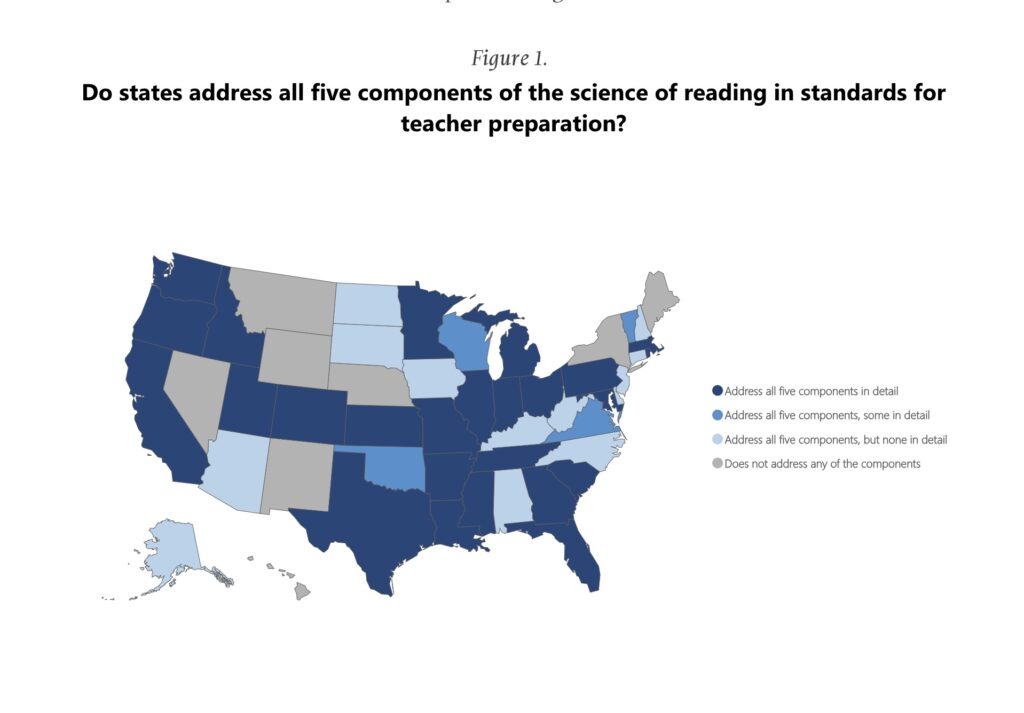

“Many new teachers aren’t prepared to teach reading because only 26 states provide clear standards to teacher prep programs,” the report attests. “Lack of specificity in standards leaves a lot up to chance.”

K12 leaders should advocate for teacher preparation standards that cover English learners and struggling readers, including students with dyslexia. Some 30 states have achieved the former benchmark while more than 40 can boast of the latter.

Explicit teacher prep standards would allow districts to get more complete information on the skills newly hired teachers have acquired. Meanwhile, 40% of states “have no way to know the quality of reading curricula in use.” And only nine states require districts to use “high-quality reading materials.”

Arkansas, for example, requires districts to select curricula from a list that has been vetted against rigorous, research-aligned standards. The state can withhold up to 10% of funding from districts that do not pick curricula from the list, the report finds.

“Without knowledge of which curricula districts use, states are missing an opportunity for instructional improvement,” the report explains. “They do not know which students are getting access to a research-backed curriculum and which students are being taught mediocre or weak curricula (more likely historically underserved students).”

K12 leaders can also lobby for more funding for professional learning in the science of reading. While more than half of states require it and provide financial support, more than half a million teachers may still not have access. “Overall, states are doing a better job at setting standards for prep programs and providing professional learning opportunities,” the report concludes. “They are further behind in embracing strong prep program approval practices, requiring a strong reading licensure test, or ensuring districts use high-quality reading curricula aligned with the science of reading.”