As voice-activated devices transition from homes to classrooms, dozens of teachers now lead spelling practice, present history lessons and interact with their students in new ways. Teachers also experiment with new modes of engagement that students will see in their professional lives.

Fifth-graders in Rayna Freedman’s classroom at Jordan/Jackson Elementary School in Massachusetts ask Google Home to describe the five states of matter—because their old science textbooks only listed three. They also play a geography game called “Where am I?” that gives clues about a location.

“In our outdated social studies books, the map of Russia is wrong,” says Freedman. “The world has changed and so have the standards. Students need to learn these online skills.”

‘Googler of the Day’

Freedman, whose elementary is part of Mansfield Public Schools, first realized the potential of voice-enabled devices when she noticed students speaking to their Chromebooks. They’d lean down and whisper, “OK, Google,” while searching a term, she says.

“I tell parents to imagine their 10-year-olds working in a law office in 20 years, where they’ll be at a desk with a computer and no keyboard,” she says. “If we don’t teach them how to talk to these communication devices to get the information they need, how are they going to do it when it becomes part of their professional lives?”

At the same time, Freedman acknowledges the privacy concerns that come with these devices. She runs her smart speaker from a “clean” Google account that is blank—other than the connection to the device—and is not linked to her identity, billing information or any student data.

Sidebar: 10 ways to use voice-activated devices in the classroom

She and her students also crafted a responsible use policy. The class leaves the Google Home unplugged when it’s not being used, and they turn it on only for educational activities—not for music or “connected home” operations such as turning off the lights.

At home, Freedman adds, most users leave voice-enabled devices on during the day, which allows the devices to record continuously.

By unplugging their device, Freedman and her students make a conscious decision to restrict potential recordings to the moments when they use the device to ask a question.

Freedman also appoints a “Googler of the Day” who is in charge of plugging in the device when someone has a question, asking that question, and then unplugging and storing the device when the activity is over.

“We say we’re secret agents training for the FBI,” says Freedman, who’s also president of MassCUE, the state chapter of the national edtech training organization. “If they leave the device plugged in, they lose their status as Googler of the Day and learn the healthy consequences.”

English language learners, who often use Google Home to ask the meaning of words, have shown a particular affinity for the device. They’d rather ask it for help than ask the teacher, Freedman says. Since the device is set up in a corner of the room, it feels more private and less embarrassing than asking a “dumb” question in front of the entire class.

“We shouldn’t be afraid of this technology, and students need to have these conversations,” she says.

Voice-activated devices capture attention

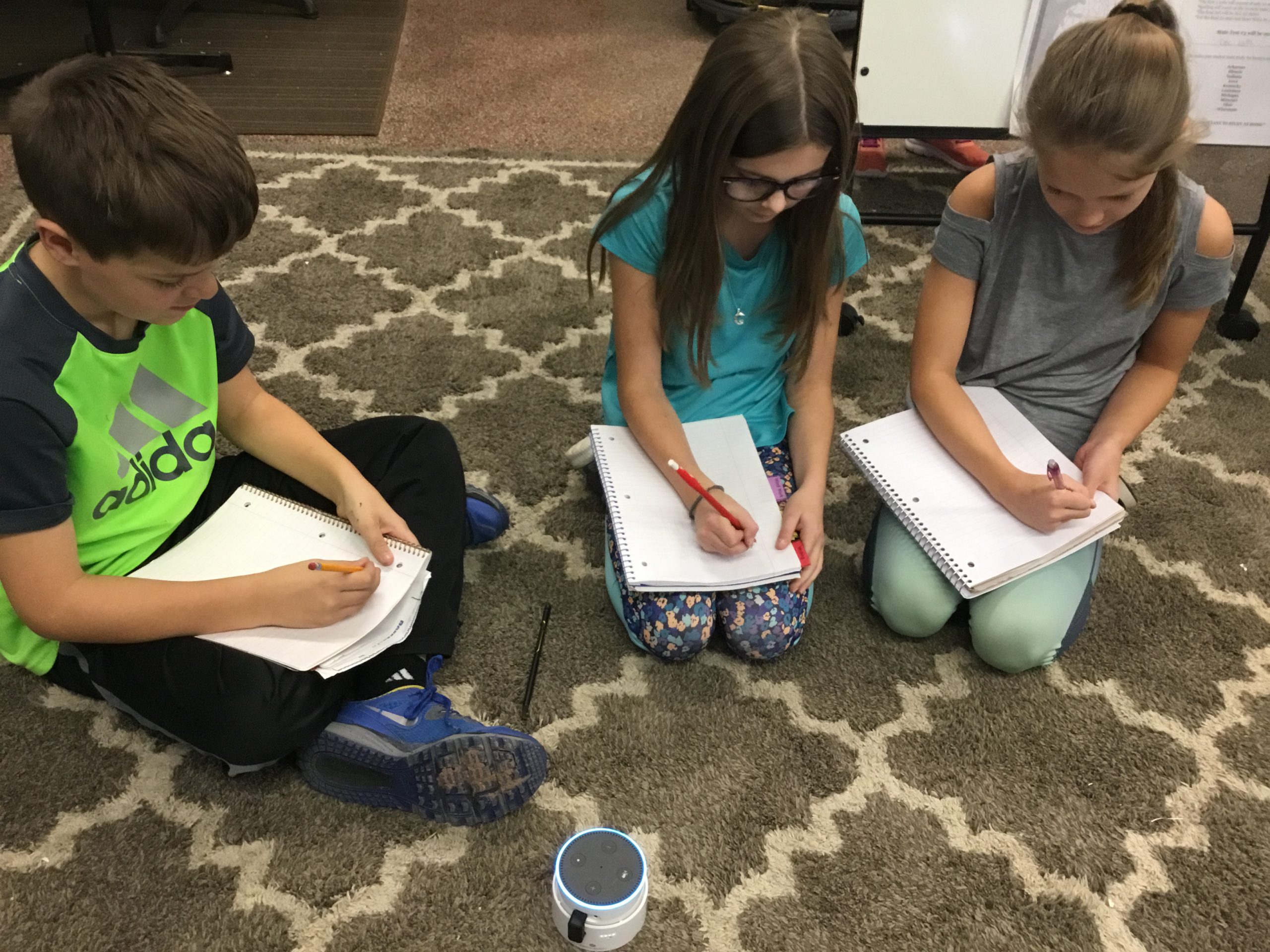

Many teachers also use voice-enabled devices to increase engagement and build listening and speaking skills. Erin Ermis, a fifth-grade teacher at Spring Road Elementary in Wisconsin’s Neenah Joint School District, uses Amazon’s Echo Dot to deliver her prerecorded morning announcements, assign writing prompts suggested by the device, and launch the math portion of the day with a number warm-up game.

Sidebar: Safety and privacy do’s and don’ts with voice-activated technology

“Simply put, I don’t hold the students’ attention the way the device does,” Ermis says. “If Alexa gives a math word problem, they’re going to be quiet and write it down.”

Amazon’s devices, in particular, use third-party apps, known as “skills,” that focus on education. Two popular skills—ClassAlexa and Ask My Class—feature critical thinking prompts, spelling and math games, and brain breaks that teachers can use to lead students through refreshing movements between lessons.

From kindergarten to high school, educators want to balance privacy with student enthusiasm for the devices’ capabilities, says Patrick Hales, an assistant professor of education at South Dakota State University who has been studying voice-enabled technology in education.

His graduate students tested Amazon Echoes in classrooms at Brookings School District, using the devices for spelling, word and math games, and classroom management tasks such as setting reminders and timers. In a high school German class, students conversed with the device, which served as a native speaker. However, younger children with speech difficulties found the device more frustrating because it couldn’t understand their questions.

“To me, this is like the move from overhead projectors to LCD projectors,” Hales says. “It’s another piece added to the classroom that could be valuable, but it doesn’t take the place of the facilitator in the classroom.”

Uncharted territory in artificial intelligence

Depending on the district, teachers bring in devices or schools provide them. Similarly, teachers in some districts connect devices to mobile hot spots, while others must use secure school networks.

Teachers who use their own devices have a better understanding of the technology. And while schools can monitor more closely devices they provide, connecting them to district networks risks data breaches.

The IT team at the Metropolitan School District of Wayne Township in Indianapolis prioritizes security as students in one classroom ask Alexa fact-based questions.

Amazon and Google are becoming more aware of education-related uses and may soon better cater to the market, but in the meantime, the district is being vigilant about user policies, filters, and state-funding requirements for secure networks.

Wayne Township’s device connects to a separate internet-of-things Wi-Fi network that doesn’t cross data with servers that contain sensitive information. Other district devices, such as credit card readers that require an open connection to the internet, are also on this separate network.

“This is uncharted territory,” says Robbie Grimes, the e-learning specialist in the district’s IT Services Department. “When the user is a minor, that raises some major questions about data and user access.”

Eujon Anderson, the technology coordinator for Troy City Schools in Alabama, says his district initially shied away from the devices, due to privacy and logistical concerns. This year, however, about 30 teachers are piloting devices for spelling drills and math problems in lower grade levels and for research in the upper grades.

Anderson trains teachers how to use the devices, including checking the voice recordings regularly to monitor how they are being used.

“Two years ago, we were never going to put Alexa in the classroom, and now I’m getting into conversations with my peers on the security side asking how it’s working,” he says. “As long as we have policies in place and conversations with parents, I think we’re going to see schools use these devices in the same way as Chromebooks.”

Carolyn Crist is a writer in Athens, Georgia.