When I first used trauma-informed practices five years ago, I experienced a change in both how I worked with kids and how I taught others to work with kids.

After an unusual end to the spring semester and an equally different back-to-school season, it’s important to recognize that new stressors will lead to increased trauma in students (and staff), requiring a need for additional support.

Whether your district is conducting distance, hybrid, or remote instruction this year, a trauma-informed approach can support you in providing care to every student and helping them grow academically, socially, and emotionally.

In this guide, I’ll share an overview of trauma-informed practices, the impact of COVID-19 on students’ wellbeing, and how to address their needs through a trauma-informed approach.

What is a trauma-informed approach?

In the 1990s, the Kaiser Health System conducted one of the largest investigations of childhood trauma – the CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE). Researchers identified ten types of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in three categories:

- Abuse: Physical, sexual, emotional

- Neglect: Physical, emotional

- Household: Family members incarcerated, mental illness, parental separation, substance abuse, domestic violence

Related: Tackling trauma: 6 steps for enhancing student mental health care

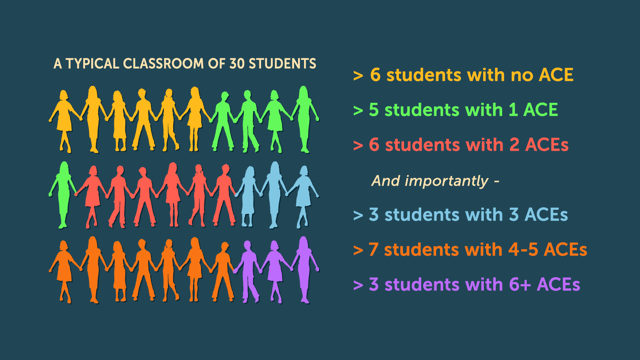

Some ACEs may feel more obvious, like physical abuse or physical and emotional neglect, but others, like witnessing domestic violence or having a family member who suffers from chronic mental illness, are equally impactful. More recent research indicates ACEs such as extreme poverty, systemic racism, and community disruption (such as a pandemic) are very prevalent. ACEs are not uncommon. In a typical classroom of 30 students, there will be six students with two ACEs, and seven students with four to five ACEs.

ACEs have been shown to have an enormous impact on students, including their resiliency, academic progress, ability to concentrate, and willingness to trust others. People with many ACEs experience higher rates of long-term health issues and early death. As kids get older, their self-worth goes down, and they gravitate to high-risk behaviors.

Educators are responsible for managing students’ behaviors on an almost daily basis. It’s crucial that we understand the link between stress and flight-or-fight response.

Consider a veteran returning from combat – a truck might backfire, and before their conscious mind is able to process what’s happening, they’re diving for cover. This same response applies to kids – there’s an angry adult in their face, and before they can say “this is my teacher, not a dangerous situation,” they are already overcome with adrenaline.

Many kids with trauma are hypervigilant in scanning for danger and have a strong social misattribution to see danger where it’s not. Low emotional regulation can make it challenging to sit calmly and work or screen out anxiety and other difficult feelings.

The importance of regulation

Students with ACEs are three times more likely to experience academic failure, four times more likely to have poor reported health, five times more likely to have attendance problems and six times more likely to have behavioral issues.

One of the biggest impacts of ACEs is a person’s ability to regulate. Regulation is the way people manage their internal state, which can be the way they think, their emotions, where their attention is directed and how they interpret and deal with their physical reactions.

Regulation is the ability to impact one’s own

- Thinking

- Attention

- Emotions

- Physical sensations

Regulation develops when two conditions are present:

- Co-regulation: Adults help toddlers and young children regulate; this repetition and modeling helps kids learn to self-regulate.

- Safe, stable environments: Kids need to be (and feel) safe and have predictable environments in order to develop regulation skills.

Kids with trauma have a more difficult time regulating emotions and are prone to becoming dysregulated.

Related: SEL priority: Students must feel safe before they can learn

COVID-19 prompts dysregulation

The current school year looks different from years prior. Kids are coming back after being out of school for six months, and they’ve been thrust into the middle of a volatile sociopolitical climate that’s included the COVID-19 virus, natural disasters such as forest fires and hurricanes protests, racial tensions, and the upcoming election cycle.

Stressful conditions in society have long been associated with increased rates of mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression, increased substance use, and higher rates of domestic violence and child abuse.

Many stressors are directly correlated to COVID-19. The fear of getting sick, concern for family and friends, social isolation, disruption of our extended family networks, loss of work and financial difficulties and stressful togetherness, including having to work and manage school for children at the same time.

Who’s at the greatest risk for increased stress?

- Children and teens

- People with underlying health conditions

- People with existing mental health conditions

- People with substance abuse disorders

- Essential workers

- People experiencing poverty

- Racial and ethnic minorities

- People experiencing homelessness

Disrupted routines

Kids have lost the routine of being in school. Those with trauma need routine in order to learn and settle in. A typical school routine helps students maintain sleep/wake cycles, follow rules, interact cooperatively with others and adhere to expectations to complete work or other activities.

Increased online time

Students have spent more time spent online and with electronics, which can lead to decreased self-control, lower emotional stability, increased distractibility and difficulty making friends and maintaining social connections.

U.S. social and political climate

When we have tensions in the greater community, kids pick up on them. Social and political tensions around the virus, mask-wearing, the appropriateness of social distancing, the murder of George Floyd and others, and the upcoming election cycle all continue to impact us in one way or another.

Related: Mental health: To screen or not to screen?

Educators, be prepared

It’s important to consider the stressors above, and remember that kids react in different ways. We have to be prepared for kids to come to school, to maybe not wear their mask, discuss racial or political issues and to prompt challenging situations.

Realize that students are coming in with tension and stress, and remember that how we talk and process it are crucial parts of how we deal with it. Remaining calm, centered and confident rather than reactive is a core part of this.

Trauma-informed approach: 4 pillars

There are four pillars of a trauma-informed approach: personal wellness, creating relationships and a sense of safety, creating predictability and helping students regulate. Let these pillars guide you in your trauma-informed practices this school year.

#1) Personal Wellness: Who you are as a person determines your success as an educator. If you aren’t calm, centered and confident, if you can’t act intentionally or are reactive to stress and problems, kids will pick up on that – especially those who have experienced any kid of trauma or are experiencing stress.

- Be grounded. Only a well-regulated adult can help a student regulate. Give yourself permission to care for your mind, body and spirit. Be aware of your own trauma and the impact that working with others who’ve experienced trauma can have on you. Remain mindful, and work to start and end the day in a regulated state.

#2) Build Relationships: Strong relationships and feeling safe heals trauma. The key element to forming relationships are presence, power and warmth. Presence is the quality of your connection with others. Power is being in charge of the classroom, and remaining confident. Warmth is having good intentions that are actively conveyed.

- Show presence, power and warmth. Show interest in students, whether it’s online or in-person. Model positive relationships, and focus on trust and safety. If students are learning online, exaggerate your non-verbal signals, and create space in your routine to check in regarding students’ non-academic interests and activities.

#3) Create Predictability: If people have a lot of trauma, are stressed out or have a lot going on, they aren’t going to respond well to surprises, and they can’t think flexibly. Students need to be able to know what’s going to happen, why, when and how.

- Follow a schedule. Develop consistent routines for each activity, and ensure that students won’t be surprised by something that could bump them into dysregulation. Continually clarify expectations for success, and maintain communication with students and their families.

#4) Teach Regulation: Coregulation means that you are using yourself to get students regulated. Remember, only a well-regulated adult can help a student regulate.

- Regulation is a shared process. Teach students how to cope with stress and uncertainty. Schedule and provide ample opportunities to regulate, and ensure learning environments feel safe and calm. Using specific words or phrases along with your routines, such as “take a deep breath” or “what feeling am I having?” can help get students where they need to be.

Prioritize trauma-informed training for all staff

Faculty, staff members and students alike are being presented with new challenges and opportunities this school year. It’s crucial that your entire school community understands the importance and value of trauma-informed instruction. I encourage you to remain intentional in planning instruction, whether it be online, in person or hybrid, start with a welcoming energy, go over the top with predictability, routine and structure, and have a plan in place for when things go awry.

For additional trauma-informed practice resources, visit https://www.321 Insight.com/.

Dr. Will Henson is a licensed clinical psychologist and a state-wide education consultant to school districts in Oregon. He consults throughout the state of Oregon on best practices for supporting students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Dr. Henson speaks and gives trainings nationwide on topics including paraeducator effectiveness, trauma-informed practices, threat management, functional assessment and best practices in supporting students with emotional and behavioral disorders. His first book Behavior Support Strategies for Education Paraprofessionals was published in 2008.