A string of student suicides over the last few years forced leaders of the Nampa School District near Boise, Idaho, to add trauma-informed teaching strategies to their approach to mental health care.

In a series of meetings with the community, administrators developed a better picture of all the traumas and tensions weighing on the minds of students: family financial difficulties, caring for siblings, academic pressure, sports and extracurricular demands, and the skewed picture of youth depicted on social media.

“We educate our kids—we give them clothing and food and dental and eye care—but we haven’t focused as closely on mental health and social needs,” Assistant Superintendent Gregg Russell says.

More from DA: Daniel Pink’s FETC keynote urges schools to rethink schedules

In adopting trauma-informed teaching strategies, Nampa’s leaders discovered what their colleagues in other districts have also learned over the last few years: Students have a greater chance of coping with traumatic childhood experiences and succeeding in class when they can turn to a trusted adult at school.

It is, therefore, important that educators excel at building healthy, supportive relationships with young people. In that sense, classroom management in an era of trauma-informed teaching must now incorporate elements of counseling, Russell adds.

“The old mentality of ‘I’m the teacher, I’m here to give students information and they’re here to receive it,’ doesn’t work anymore,” Russell says. “You need to let students know you care for them beyond the content you’re teaching, because when kids aren’t getting that kind of support from an adult, this world is a pretty lonely place.”

How to use books, movies and songs in trauma-informed teaching

Building authentic relationships is the No. 1 trauma-informed teaching strategy for helping students develop resilience against toxic stress, says Jaime Castellano, a professor who teaches classroom management and inclusion at Florida Atlantic University’s College of Education.

Trauma means teachers

must care for themselves, too

Staff wellness and empowerment constitute key elements of providing trauma-informed support to students in St. Louis Public Schools, says Megan Marietta, the district’s director of social work.

“If we have healthy staff who are able to build healthy relationships with students and families, we are going to see better outcomes for our kids,” Marietta says. “If there are approaches that are going to benefit students, they are just as likely to benefit staff.”

Eleven St. Louis elementary schools are piloting PD that guides teachers in adding mindfulness and other self-care techniques into their daily routines.

In a few buildings, educators visit classrooms with a coffee break cart. Teachers are encouraged to have a coffee or a pastry and take a 10-minute break to refresh while one of the educators covers their classrooms. Some schools also have created wellness committees to schedule time for teachers to have short counseling sessions with school mental health clinicians.

And school “regulation rooms” that have been created to provide a place for students to calm themselves have now been opened to teachers who need some quiet time.

An overall goal of these initiatives is to destigmatize the concept of teachers asking for a little assistance. Getting in a better mindset allows teachers to work more closely with families, to take new approaches to discipline and to create more equitable environments in supporting students who are coping with stress, Marietta says.

“You have to understand who your students are, where they come from, what traumas they have experienced and what might trigger inappropriate behavior,” says Castellano, who also works with K-12 students as a case manager at Multilingual Psychotherapy Centers, Inc., in Palm Beach County.

With his student teachers, he models several trauma-informed teaching activities, such as what he calls “the cultural you.” Teachers can ask students to describe the sights, sounds and smells of home that paint a picture of their cultural backgrounds. In another exercise, students bring five items that help define their identities.

On the academic side, he recommends “bibliotherapy” and “cinematherapy,” in which teachers lead discussions after classes read books and watch movies that depict some of the challenges students are facing. “This shows them they are not alone, that there are others out there who have overcome the traumas they’ve experienced,” he says.

More from DA: Are teens too sleepy to enjoy learning?

Castellano also suggests that teachers ask students to share songs that give them hope and inspiration in overcoming challenges. Ultimately, it’s critical to create a safe school environment by sticking to classroom routines and setting clear expectations for students.

“Trauma and anxiety and depression transcend zip codes and income levels,” he says. “And for every kid we identify and who is getting help, there are probably two to three kids whom no one knows about.”

Mental health supports as trauma-informed teaching strategies

In adopting trauma-informed teaching strategies, Nampa School District leaders ran up against a troubling phenomenon, says Russell.

Even when students confided suicidal or despondent thoughts to a friend, those friends often felt they had to keep it secret rather than alerting a teacher, counselor or other adult. Even teachers might hesitate to pass on such information for fear of betraying a student’s trust, he adds.

Counselors trained in trauma-informed teaching strategies treat students at mental health clinics based at seven of Nampa’s schools. These visits get documented to better assess the severity of a students’ mental state and track treatments when students switch schools within the district, Russell says.

In addition, administrators have created advisory periods in which educators meet regularly with every high school student to discuss what’s going on in their lives in and outside of school.

In the classroom, teachers this school year have focused on building students’ resilience with a range of resources, including the Second Step social-emotional learning curriculum and mindfulness apps such as Mind Yeti and Headspace. Some of these materials were purchased with a $150,000 grant from the Blue Cross Foundation.

“We’re looking at this through a number of lenses,” says Shelley Bonds, the executive director of elementary education. “But we did see a decline from a year ago in the number of major behavioral incidents in the first nine weeks of school.”

‘What if I was good at math?’

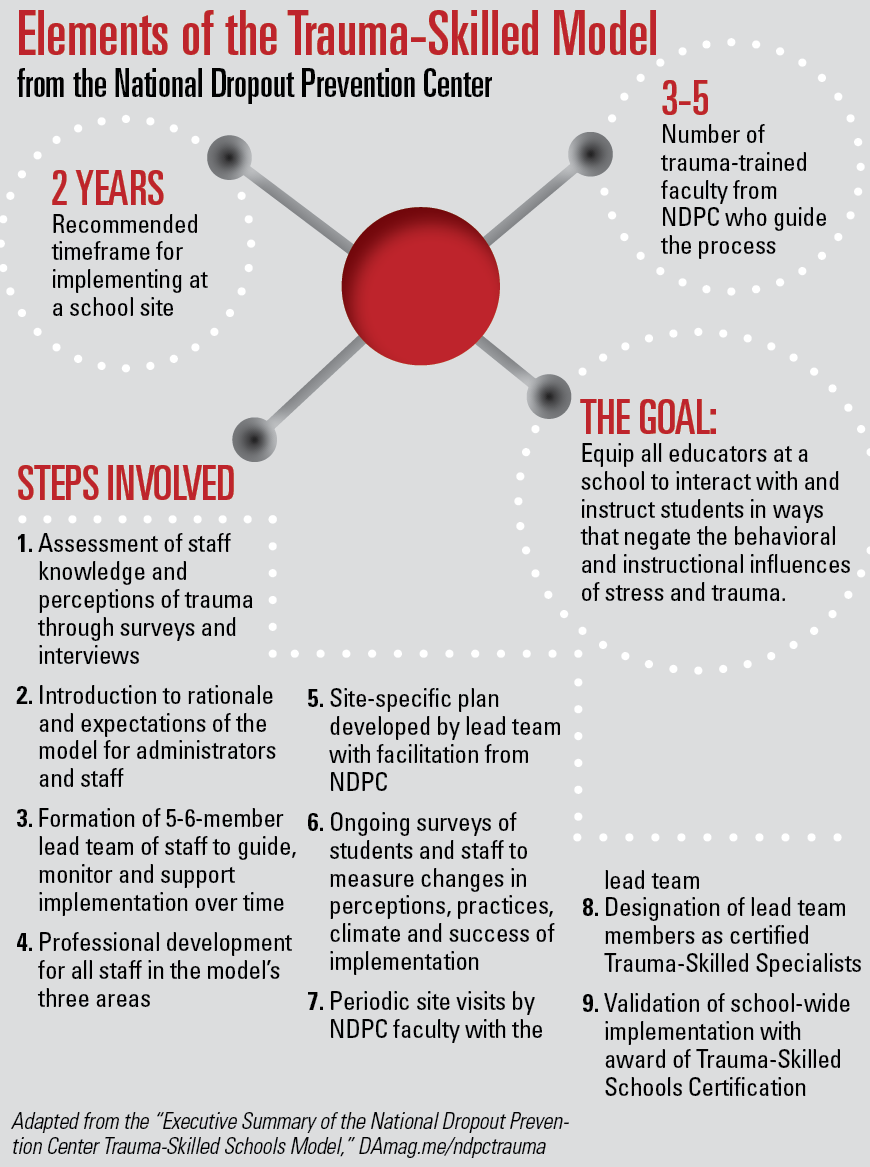

Several administrators are working to make their buildings “trauma-skilled schools” through a professional development and curricular program developed by the nonprofit National Dropout Prevention Center.

In the process, some school leaders have found teachers hesitant to add “mental health counselor” to their job description, says Sandy Addis, the center’s director.

The goal of the program, however, is for all staff—from every teacher to every bus driver—to get a better understanding of how trauma impacts students’ behavior.

Take, for instance, a student who gets shut in a closet as punishment at home. That student will likely have an adverse reaction when brought into a similarly small office to be disciplined by a vice principal, Addis says.

The center’s PD guides teachers in building student confidence by letting kids make choices, such as picking their own seats or suggesting classroom rules at the beginning of the school year.

“Kids who have been traumatized often perceive that they’re not choice-makers in their own lives,” Addis says. “A lot of times in school we unconsciously don’t give kids choice when we could very easily do so.”

At the Renaissance School, an alternative program of the Bremerton School District in Washington, becoming a trauma-skilled school means helping students envision a successful future for themselves, Principal Kristen Morga says.

More from DA: How to balance safety and stress in lockdown drills

“Students have to see their goals as realistic and attainable in order to not give up,” Morga says. “We’re working to make sure that all of our interactions are transformational rather than transactional.”

Interactions—even seemingly insignificant ones—become transformational when teachers can build on students’ strengths, she says. For instance, when a student says “I can’t do this, I’m terrible at math,” a transformational teacher says “What if you could do? What if you were good at math,” Morga says.

“Even if they don’t respond in the moment, it puts it into the kid’s brain,” she says. “They can continue to think, ‘What if I was good at math?’ It opens up a lot of possibilities.”

Matt Zalaznick is senior writer.

Engage with your peers about hot topics in teaching and learning. Attend one of DA’s 2020 CAO Summits, March 18-20 in Dallas, October 12-14 in Chicago, or November 16-18 in Long Beach, Calif.