As districts and schools step into the final planning period before reopening – virtually, in-person, or in hybrid models – we’re forced to confront gaps in our planning and areas to deepen in crisis preparations. Over the last several months, Chiefs for Change and the Council of Chief State School Officers partnered to lead a series of webinars and workshops to help district and state leaders respond to the public health crisis and build plans that keep kids learning safely.

In an earlier piece, we highlighted the need for districts and individual schools to conduct day-in-the-life simulations to identify gaps in their reopening plans. Today, we are sharing an overview of organizational structures and decision-making processes needed to respond nimbly to changing conditions and the needs of students, teachers and the broader system over the next year, all with a focus on preparing for a remote Fall.

It is hard to believe that the cascade of districts deciding to close and pivot to distance learning was only four months ago. District by district, as schools across America closed, educators, students, and parents have been thrown into a new and evolving frontier of remote and digital learning without an instruction manual. Even today, there are still more questions than answers about the virus, our economic future, and how public education will look in our country in the year (and years) ahead.

When an organization is pushed into crisis mode, there are four factors that tend to impede a response:

- Inadequate discovery: As hard as it is to imagine at this moment in time, an optimism bias is in nature. That bias can create blinders during discovery and hamper our ability to fully assess the situation we face.

- Constrained solution design: Many organizations have concrete boundaries that have been shifted – or shattered – by crises and require completely new solution designs to tackle them.

- Slow or bad decision quality: Every large organization – including school districts – can fall victim to group-think, political pressures, and highly emotional feedback loops from individually impacted constituents that can slow decisions or – worse – lean on populist consensus forged without expertise.

- Inadequate delivery: During a crisis, chaos and uncertainty are constant and without clear crisis plans, this chaos can translate to lack of direction and lack of accountability.

(Click to enlarge the images below, then click your browser’s Back button to continue reading)

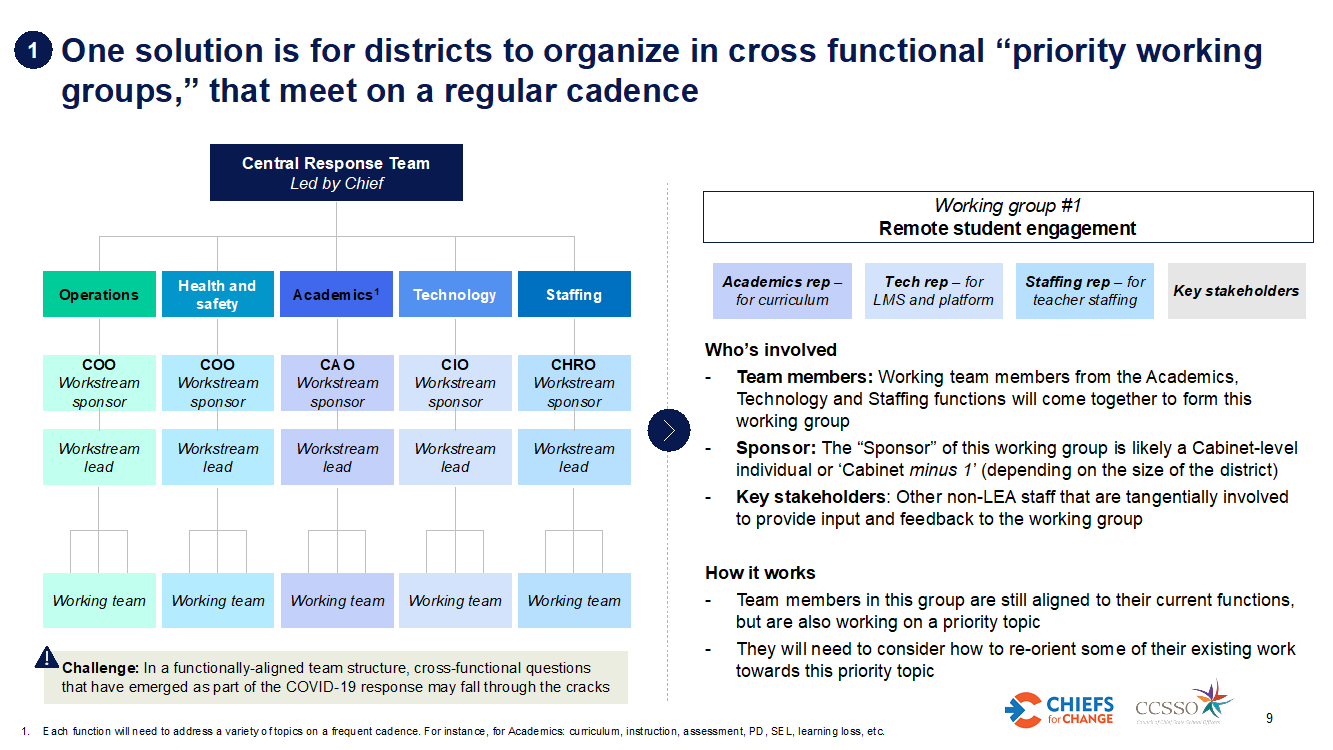

There is a big difference between the immediate crisis we faced in March and April when cities, states and whole economies shut down overnight and the longer-term challenges we face today in continuing operations in our schools this year. That initial crisis required a rapid response and mitigation. Through it, we exposed significant gaps that must now be reflected in our reopening plans and throughout this school year. Many of those gaps were organizational and it hampered districts’ crisis response because the burden of decision making and action fell too narrowly on a small group of people. This puts districts at risk of group think and puts leaders at risk of burn out. With the crisis contained, now is the time to develop and tone the muscle memory required for teams to operate at two speeds and – as importantly – snap back into crisis mode at a moment’s notice.

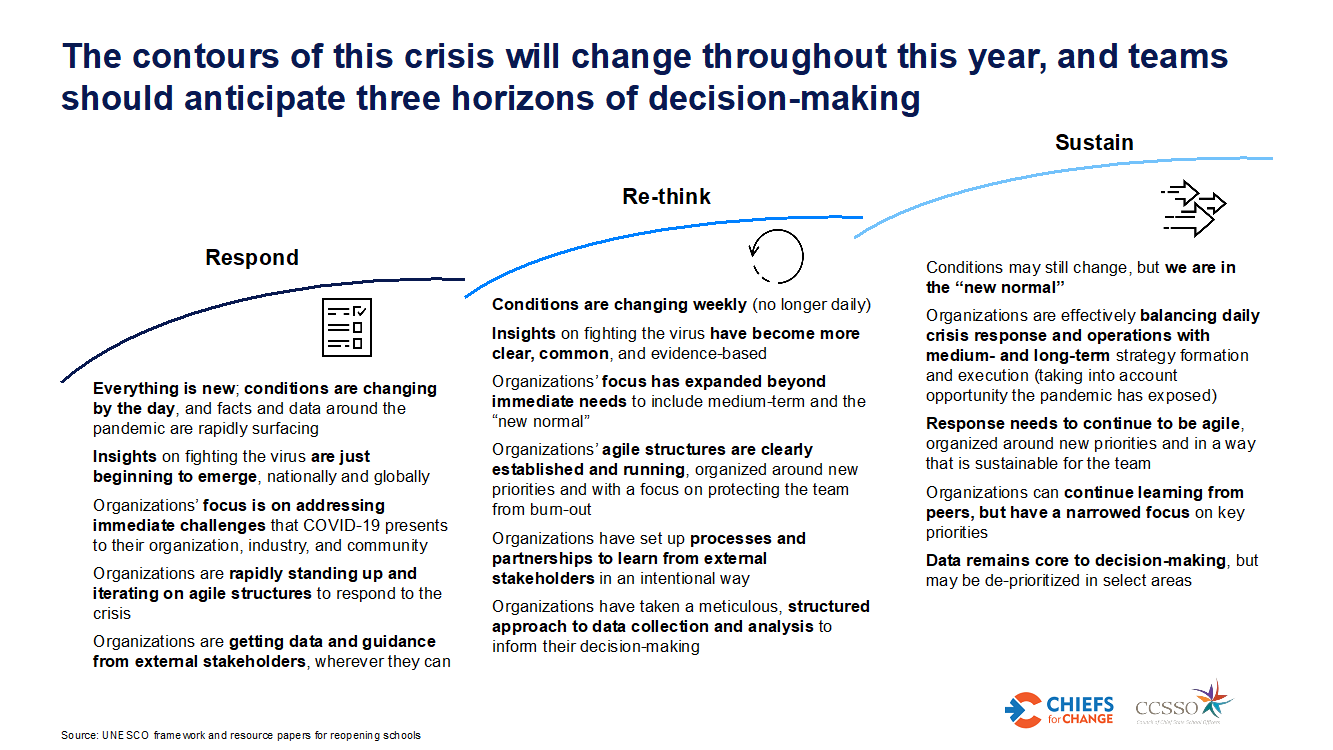

The contours of districts’ plans and the public health crisis will change over time, and leadership teams should anticipate and prepare for three horizons of decision-making: responding, re-thinking, and sustaining.

Any district’s response to COVID and implementation of any reopening plan is going to require a long-term response. And there are factors districts need to consider to ensure their team is equipped for the long haul. First, organize teams to focus on the problems, not by historic roles. Second, data is critical and needs to be constantly monitored. Third, prepare your team to operate at two speeds that balance immediate responses with longer-term strategic priorities. Fourth, maintain external orientation to continue learning. And lastly – and perhaps most importantly – monitor the pace of work to avoid team burn out. This pandemic requires the endurance of an ultramarathon.

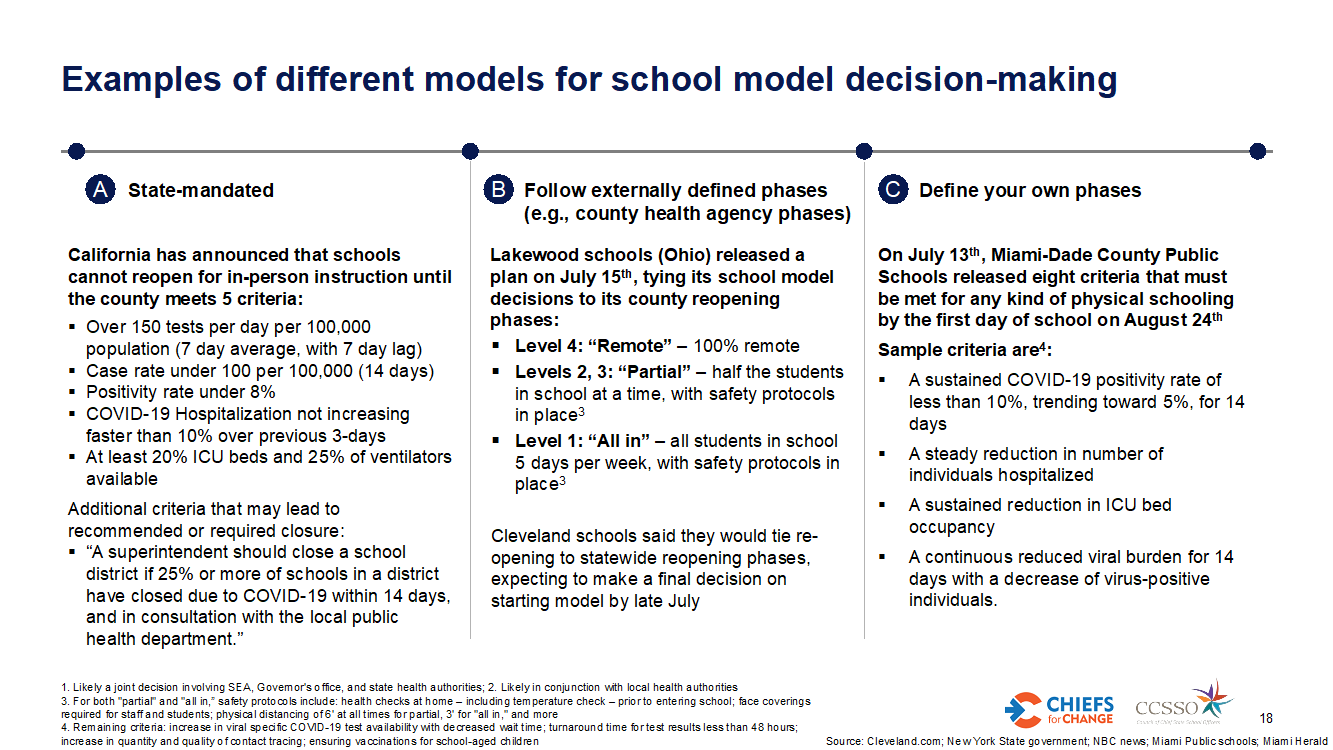

With this focus on crisis preparation and planning, districts will be better equipped to implement reopening and remote-learning plans. And every district is tackling this effort with different guidelines and inputs – some from state mandates, some built from community processes, and some entirely internal.

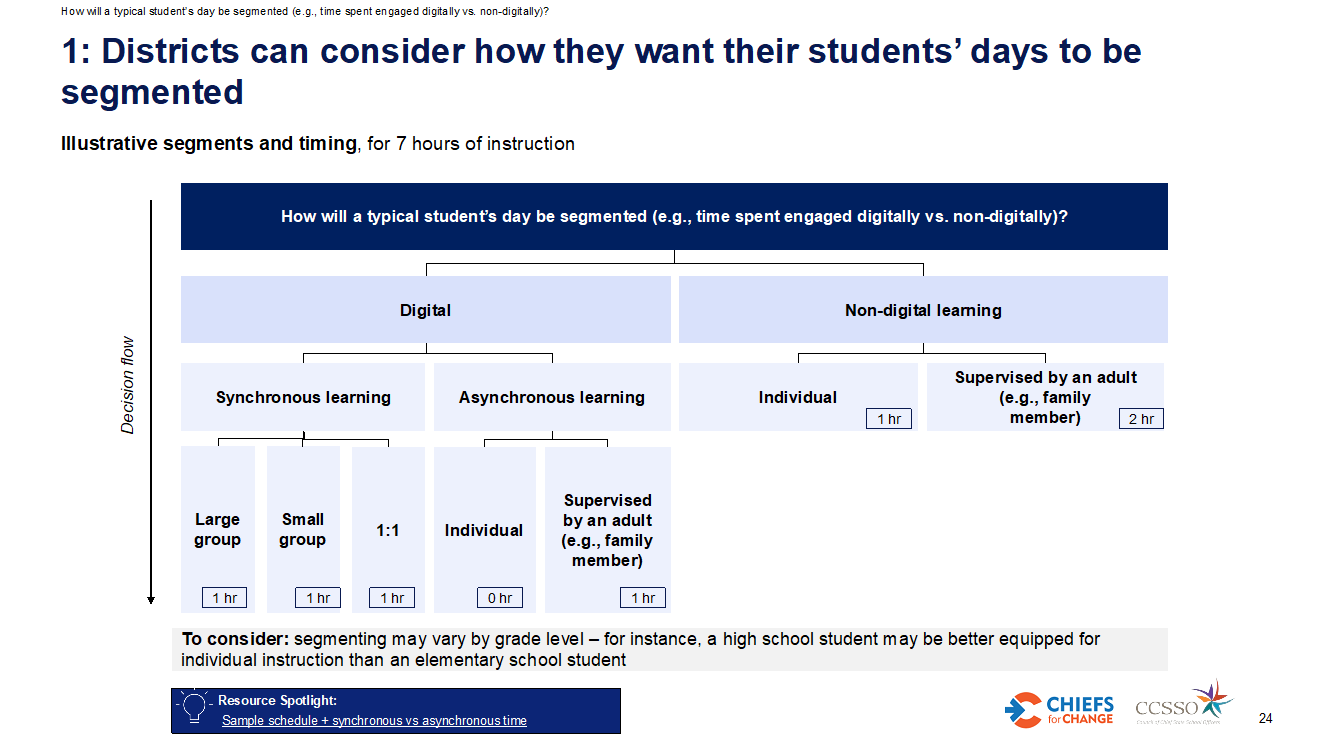

As districts make the informed decision of their reopening model, the path for success again turns to preparations, simulations, and a commitment to accountability. Let’s focus on remote learning.

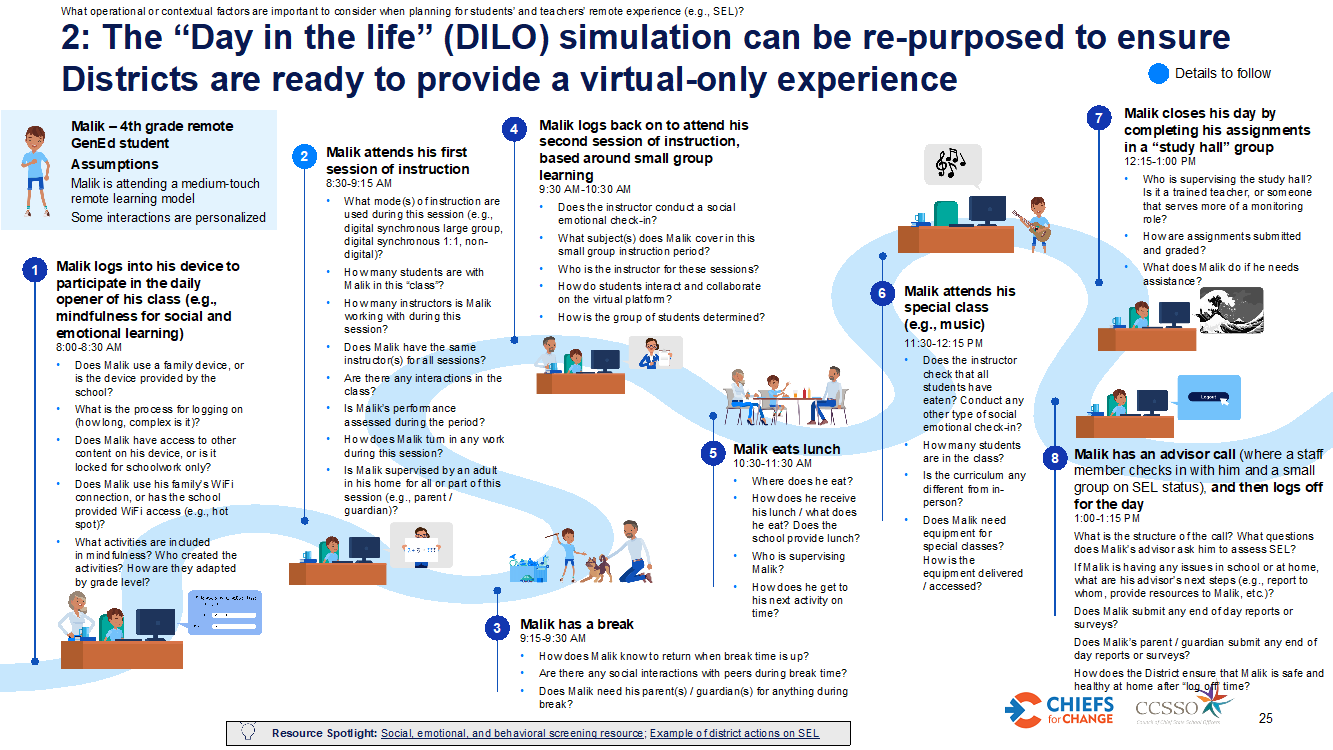

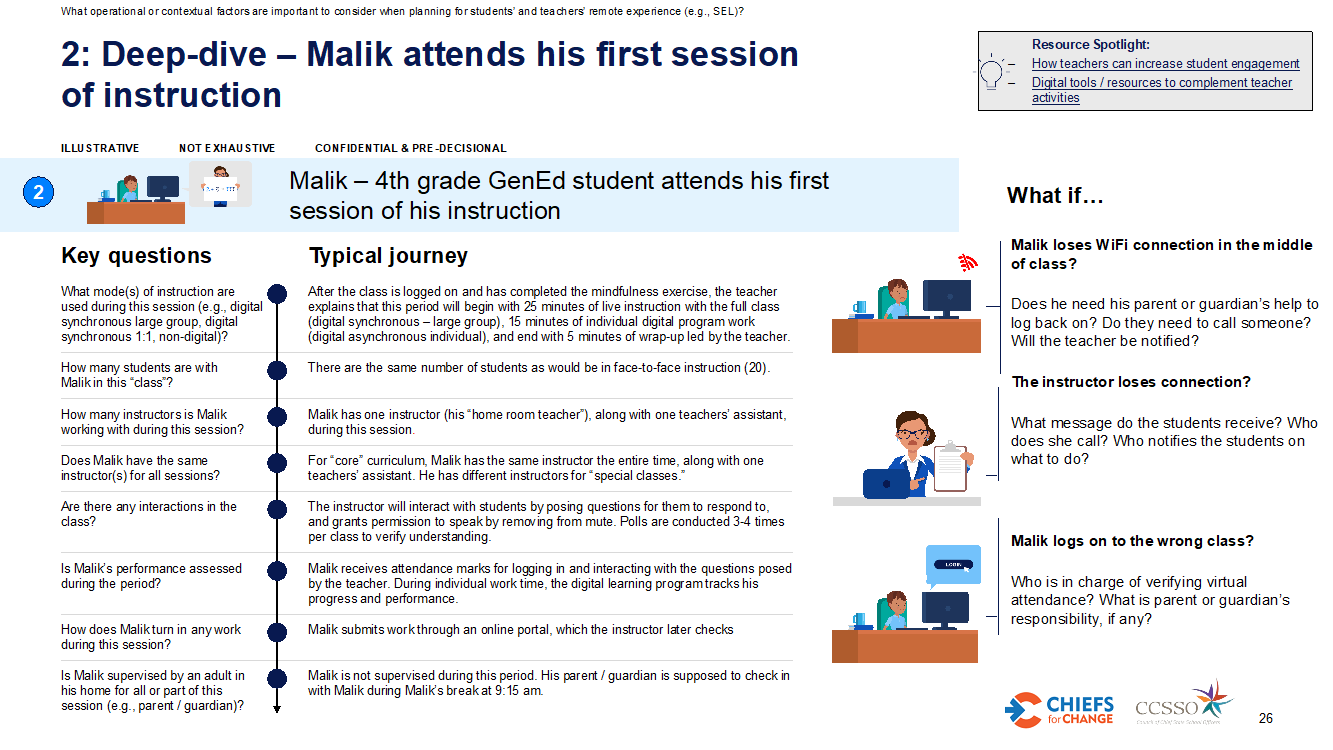

To understand how districts need to reopen, we’ll bring our hypothetical student, Malik, back into our discussion.

Malik is a fourth-grade student attending a remote learning model. At 8 a.m., he logs into his device for his class’s morning meeting – an opportunity for some connection with classmates and his teachers and morning mindfulness activities.

But the running list of questions about how he engages begins immediately:

Is he using a family device or one provided by the district? What’s the process to log on? How long does that take? How complex? Are there passwords?

What about the content? What activities are included in mindfulness?

Is his device locked to focus only on school materials or can he access other external sites and content?

Throughout the day, Malik will toggle between live and asynchronous learning. Each part of his day requires districts and school leaders to map different scenarios that range from what kind of at-home support is available to Malik, to how he will get lunch. The ‘what if’ questions are indeed the most important because they help expose key gaps that can derail well-intentioned and seemingly thorough plans.

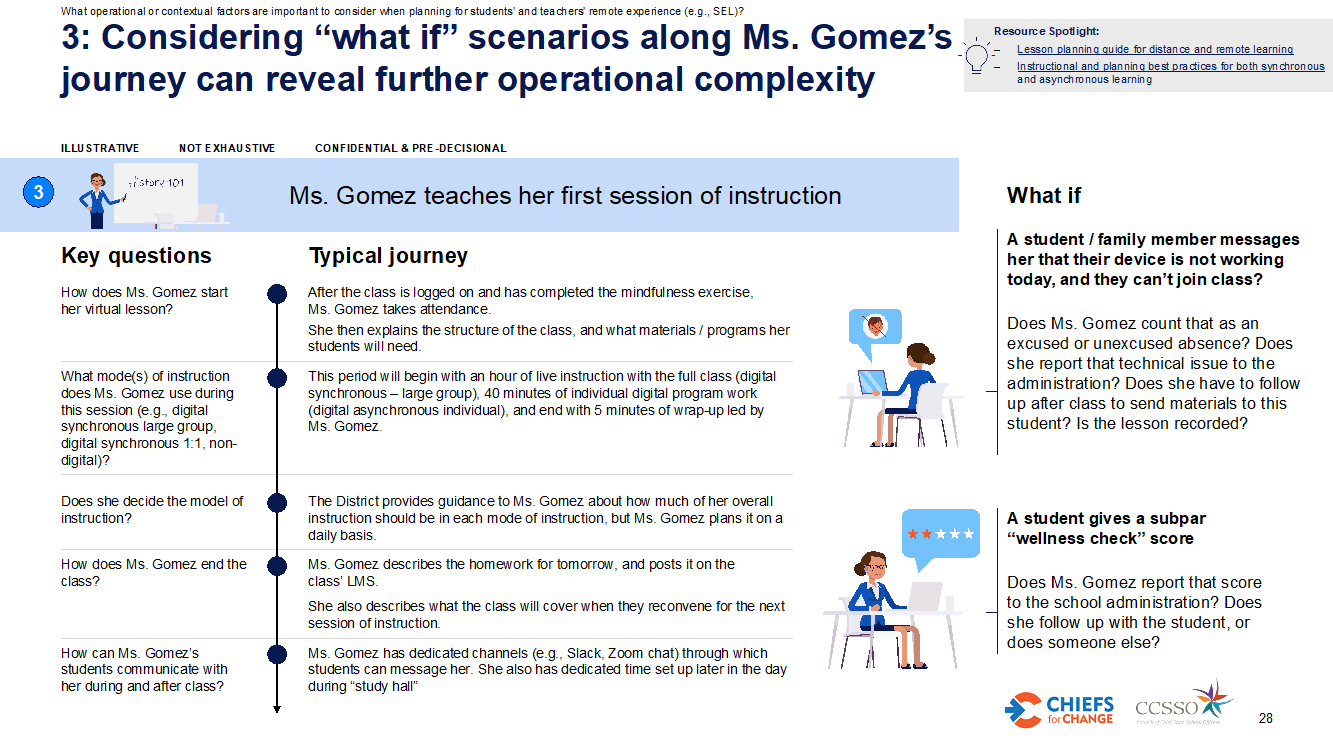

Districts need to put students first in their planning, and doing so requires the same level of attention to the day-in-the-life of their teachers. In our workshop, we focused on Ms. Gomez, a fifth-grade teacher teaching her class from her home. The questions we need to consider here range from instructional (“What model of instruction does Ms. Gomez use?”) to administrative (“Is Ms. Gomez allowed to be ‘offline’ during a break?”) to psychological (“How does Ms. Gomez conduct social-emotional check ins?”).

Districts need to put students first in their planning, and doing so requires the same level of attention to the day-in-the-life of their teachers. In our workshop, we focused on Ms. Gomez, a fifth-grade teacher teaching her class from her home. The questions we need to consider here range from instructional (“What model of instruction does Ms. Gomez use?”) to administrative (“Is Ms. Gomez allowed to be ‘offline’ during a break?”) to psychological (“How does Ms. Gomez conduct social-emotional check ins?”).

And even those simulations fail to take into account questions about the gaps Ms. Gomez may face at home: Are her children learning remotely? What devices and internet bandwidth does she have? Does she have a dedicated space in her home to teach?

And even those simulations fail to take into account questions about the gaps Ms. Gomez may face at home: Are her children learning remotely? What devices and internet bandwidth does she have? Does she have a dedicated space in her home to teach?

We can’t expect to have all the answers: There is not a single person among us – in education, business, or government – who has lived through a disruption of this magnitude. As we wrote last month, no plan is going to predict every possible scenario with perfect precision, and districts will run into challenges. But organizational leaders have an obligation to build muscle memory within their organizations – through repetition and practice – that can flex to meet the demands of any challenge. This means intentionally creating the systems and structures that ensure when questions come up that have not been answered that we at least know the process internally within our teams for how to get to an answer. The resources we’ve developed and made available throughout this crisis have aimed to tone that muscle memory. All of our materials, case studies, and updated best practices are available in our digital report, Schools and COVID-19: How Districts and State Education Systems are Responding to the Pandemic.

If there is an instruction manual for reentry, it’s written in sand. But with proper planning, research, and objective flexibility, districts can provide parents, students, and teachers with ease of mind that even while 2020-2021 will look very different, it will not be a lost year.

Dr. Julia Rafal-Baer is the chief operating officer of Chiefs for Change, a bipartisan network of state and district education chiefs. A former assistant commissioner at the New York State Education Department, Rafal-Baer earned a Ph.D. in education policy from the University of Cambridge, where she was a Marshall Scholar. She began her career as a special-education teacher in the Bronx.

Dr. Peter Gorman is Chief in Residence with Chiefs For Change, executive coach for superintendents and senior leadership teams, and the author of the book, “Leading a School District Requires Clarity, Context, and Candor: An Aligned System to Increase Student Achievement at Scale.” He is the former Superintendent of the Tustin Unified School District and Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools in Charlotte, North Carolina.