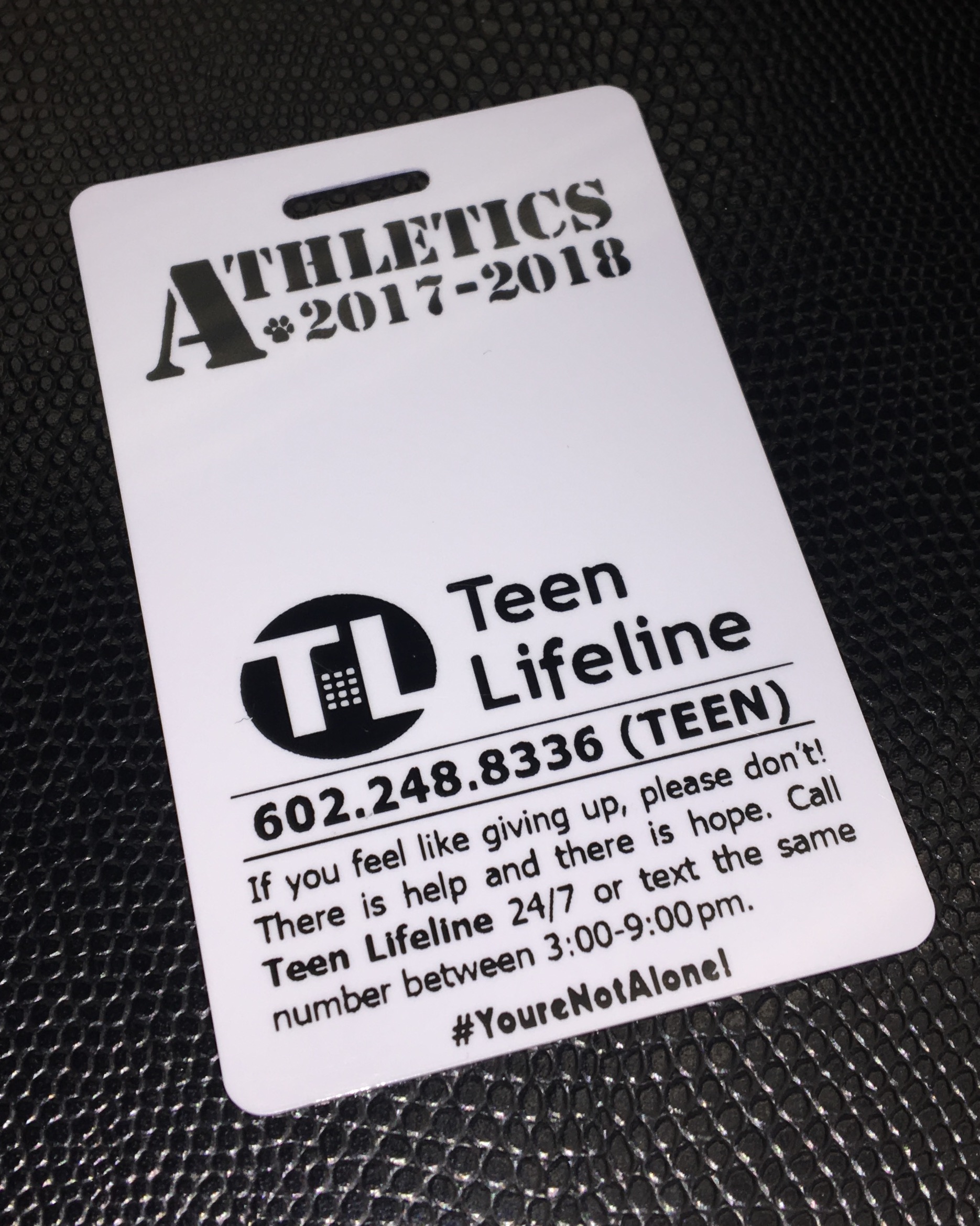

In Tempe, Arizona, the phone number for a suicide hotline is printed on every student’s ID badge, teachers are trained to spot and respond to mental health warning signs in students, and administrators don’t use euphemisms when discussing the topic.

“We can’t tiptoe around the word ‘suicide’ by saying someone ‘took their life’—it’s death by suicide, and we have to call it what it is, as harsh as it sounds,” says Kevin Mendivil, superintendent of the Tempe Union High School District. “It resonates when it’s verbalized by a caring adult because it’s what’s going on in kids’ heads.”

What’s happening in Tempe is happening across the country, as new school district suicide prevention efforts focus on getting help to students before they reach the crisis stage. As part of that work, districts large and small have hired more school psychologists and counselors, and have formed partnerships in which local mental health care agencies supply additional therapists and resources.

Other district leaders have expanded mental health screenings—in some cases to the entire student body. And because young people are more likely to reach out to their peers, a few districts have trained groups of students to notify teachers or other educators when a classmate needs immediate assistance.

“Make sure that mental health is incorporated into all things that happen throughout the year,” says Daniel J. Reidenberg, a psychologist and executive director of Suicide Awareness Voices of Education. “People can’t just talk about mental health in response to something bad happening.”

Mental health screenings spot suicide risk

After three students in Olathe Public Schools committed suicide in the 2017-18 school year, the suburban Kansas district conducted mental health screenings of all 12,000 students at its seven high schools.

The district purchased the SOS Signs of Suicide program to educate students and assess them for risk of self-harm. The one-day program included surveys that asked students whether they or any friends were considering suicide, says Angie Salava, the district’s college and career readiness and counseling services coordinator.

Read more: 5 keys to caring for mental health and suicide

Students who responded that they needed help right away were seen that day by one of 25 volunteer therapists from the surrounding community. On the survey, students could also indicate that they weren’t in immediate crisis, but wanted to receive counseling.

“The majority of students were not critical, but we did hospitalize 14 students on the days of implementation—about two per school,” she says. “This program has saved lives.”

Olathe Public Schools Superintendent John Allison has also teamed up with leaders of several surrounding districts in a coalition that uses the hashtag #ZeroReasonsWhy to reduce the stigma around seeking mental health counseling. The hashtag counters the impact of the controversial Netflix series 13 Reasons Why. In turn, students have been inspired to form #ZeroReasonsWhy groups to spark more open conversation about suicide.

What’s a real panic attack?

Students in the Lakota Local School District in Ohio also play a key role in suicide prevention. In spring 2018, Lakota East High School students formed a Hope Squad based on a model created in Utah. Students, who are nominated by their peers to join the program, make it known via social media and other publicity campaigns that they are available to talk to students who are suffering.

“They are the eyes and ears of our school,” Principal Suzanna H. Davis says. “Many students feel unbelievably comfortable going to the Hope Squad.”

Read more: Suicide prevention program focuses on LGBTQ students

Hope Squad members train to use “Question, Persuade, Refer” techniques (also known as QPR) when speaking to classmates in distress. In January, a student on the verge of self-harm contacted a Hope Squad member, who connected that student with a counselor. In December, several Hope Squad members notified administrators that they were extremely concerned about a student off campus. The school contacted police, who responded quickly and took the student for medical treatment.

“Conversations about suicide among students are not new,” Davis says. “What is new is that our students feel empowered to do something with the information.”

In Indiana, students at Hamilton Southeastern Schools’ two high schools formed Bring Change to Mind clubs to reduce the stigmas around mental illness and to encourage their classmates to seek help.

Students in the club study the symptoms of mental illnesses so they can share those lessons with their friends. They learn, for instance, the major differences between a young person who has bipolar disorder and someone who is just moody. “One thing that perpetuates the stigmas is not understanding the language being used,” says Brooke Lawson, the district’s mental health and school counseling coordinator.

“If you’re just feeling nervous and think you’re having a panic attack, that can devalue the experience for someone who is really having a panic attack.”

In eighth grade, students take a unit on suicide. They must identify three adults whom they would go to if they had suicidal thoughts or knew a friend was in danger.

“We want students to be equipped to know how to handle problems,” Lawson says. “We tell students it’s not their job to get peers the help they need; it’s their job to tell an adult.”

Creating safe spaces

When a graduate of Hamilton Southeastern Schools committed suicide in 2013, the former student’s family members used donations they received to help the district launch the Peyton Riekhof Foundation for Youth Hope. Its mission is to prevent self-harm and suicide, and encourage students to seek mental health treatment.

The foundation’s first initiative entailed training all high school and middle school teachers to identify and respond to students who are having suicidal thoughts, Lawson says.

The district then used money from a voter-approved referendum to add a mental health therapist to the counseling teams at each of its 21 schools. Therapists can refer a student for hospitalization and create an ongoing safety plan.

DeKalb County School District, a diverse district in the Atlanta suburbs, has focused its suicide prevention efforts on professional development. With 135 schools and 14,000 employees, that training has come in many forms, says Deputy Superintendent Vasanne Tinsley.

The district has brought in community agencies to deliver the training as it is being requested by more and more principals. “This is not always something teachers get in basic training,” Tinsley says. “It’s important because a lot of times students begin acting out in the classroom, and that can lead to self-destructive behavior.”

Teachers and support staff learn that anxiety, depression and peer relationships can all fuel disruptive behavior. They also practice de-escalation techniques to try to calm students. “We’re helping them establish a rapport with their students,” she says.

“We’re helping them develop safe spaces in their classrooms.”

Every kid needs a caring adult

Tempe Union High School District, which lost a student to suicide in November 2017, also ramped up training for all teachers as part of a more proactive approach to meeting students’ social-emotional needs.

These efforts include some simple actions that make a positive difference in students’ lives, such as teachers welcoming students by name at the door, and getting to know the students and asking them about activities they’re involved in, says Mendivil, the superintendent.

This creates an environment in the classroom where there’s more dialogue, which is important, particularly at the high school level, he adds. “It’s the kind of caring you would see in an elementary or a junior high,” he says. “We have content we’re delivering to students, and we sometimes lose the notion that we’re dealing with children who still need to understand that their teachers care for them.”

Tempe’s educators and staff also have become more “situationally astute,” which includes feeling comfortable enough to ask a student if they are contemplating suicide or walking a student to the counseling office, he says. Teachers and staff also check on the emotional states of students whose grades, attendance or behavior slip.

“We’ll have lots of eyes on a kid to make sure they’re in a safe spot,” Mendivil says. “We’ve got to make sure that every kid has a caring adult in their life while they’re with us.”

Matt Zalaznick is senior associate editor.