The first article in this series introduced the concept, “tyranny of or,” focusing on limitations of traditional item analysis in English language arts. In this follow-up, we delve deeper into modern item analysis informed by the science of reading to improve data-driven instruction and reading achievement.

We explore real-world scenarios where educators encounter challenges interpreting item analysis from standards-based ELA assessments and use these examples to illustrate effective diagnostic approaches. Commentary follows, culminating in a set of guiding principles to optimize use of item analysis data in ELA.

Scenario 2: Identifying Student Errors & Profiling Student Strengths & Weaknesses

Mrs. Profile Pinpoints Intervention

Javier, a multilingual first grader, completes the STAR Phonics assessment, designed to highlight strengths and weaknesses across phonics categories. Upon review, Mrs. Profile notices several students, including Javier, struggle with decoding common vowel teams—a skill aligned with standard RF 2.3. Since these students have mastered simpler CVC words, Mrs. Profile focuses on targeted instruction to address their needs.

To pinpoint the specific vowel teams causing difficulty, Mrs. Profile administers a STAR Phonics Diagnostic for vowel teams. The results suggest Javier needs additional support with the vowel teams “oi” and “aw.” While refining instruction can be challenging, this item analysis gives Mrs. Profile a clear direction on tailoring her approach and enhancing Javier’s reading skills. A few months later, her targeted intervention pays off as Javier shows significant progress.

In this scenario, Mrs. Profile used item analysis from the diagnostic assessment to provide just-right support to close phonics skills gaps and ensure Javier had the decoding skills to access grade level texts. When educators have data profiles pinpointing students’ errors, then they can deliver interventions and assign purposeful practice to prevent students from making the same mistakes (Kern & Hosp, 2018). Vowel teams? Checked off!

Scenario 3: Identifying Objectives or Standards Not Mastered

Mr. Stan R. Mastered Adjusts Alignment

Mr. Stan R. Mastered, a seventh-grade ELA teacher, reviews state assessment results and notes his students performed below the state average on standard RL 7.3, which involves analyzing interactions between story elements. This low performance is consistent across multiple years. Puzzled, Mr. Mastered investigates a released assessment question expecting it to focus on setting, but instead, the question asks what the contrasting descriptions of two towns reveal about a character’s feelings.

He realizes the question is not about identifying setting; it’s about analyzing how setting impacts the character’s emotions. His classroom activities involve identifying and describing settings—a fourth-grade skill—rather than analyzing how setting influences plot or characters, as required by the seventh-grade standard. To bridge this gap, Mr. Mastered researches strategies to align his instruction better with RL 7.3.

This scenario highlights the importance of using item analysis to identify gaps in standards mastery and ensure curricular alignment with grade-level expectations. Diagnosing misalignment allows teachers to adjust instruction to meet grade-level expectations, ensuring students spend time on appropriate, challenging tasks (Moore, Garst, & Marzano, 2015; TNTP, 2018).

One advantage of this diagnostic approach encourages deep examination of grade-level standards and facilitates cross-grade conversations to support vertical alignment (Moore, Garst, Marzano, 2015) as students often spend over 500 hours per year on assignments that are not grade-appropriate (TNTP, 2018) By refining his approach, Mr. Mastered aims to close curriculum gaps and elevate student performance. Alignment adjusted!

Scenario 4: Identifying Student Knowledge Structures

Mrs. Dee Mand Raises Rigor

Curriculum director Mrs. Dee Mand examines fifth-grade state test results and notices a puzzling outcome: only 25% of students answered one item on standard RL 5.6 correctly, while nearly 100% answered a second item correctly. The district’s mCLASS data, as well as common assessment scores suggest students mastered decoding skills.

Investigating further, she finds that both items are based on the same passage but differ in cognitive demand. The first item, a DOK level 3 question, asks, “How does the author develop the speaker’s perspective throughout the story?” The second, a DOK level 2 question, asks, “How is the speaker’s perspective developed in paragraph 2?”

Realizing her district’s previous assessments only included lower-level DOK questions, Dee Mand collaborates with teachers to integrate higher-order thinking into instruction. The following year, after focusing on deeper cognitive skills, state results improve significantly: nearly 100% of students correctly answer DOK level 2 questions, and 65% meet DOK level 3 expectations—up from 25%.

This scenario illustrates how Dee Mand utilized item analysis to examine students’ knowledge structures and cognitive processing. By initially ruling out foundational skills issues through the SoR lens, she identified a gap in how instruction was addressing cognitive demand (Hess, 2018; Popham, 2020).

Cross-referencing data allowed her to pinpoint that the focus needed to shift toward teaching students to apply knowledge at higher DOK levels to enhance comprehension (Moats, Tolman, & Paulson, 2019). This approach raised test scores and increased the likelihood students would transfer their knowledge to non-routine contexts (McTighe, 2014; Steiner, 2023). Rigor raised!

Commentary and analysis

The scenarios in this series illustrate the diagnostic power of item analysis when combined with an understanding of the SoR. Each educator analyzed foundational skills, addressed skills gaps, and corrected instructional alignment to tailor interventions effectively.

Consider what Mr. D. Per did. He discovered his students had unresolved phonics gaps and did not just practice comprehension skills. Mrs. Profile used a student’s diagnostic phonics data to target support for Javier. Mr. Mastered determined his instruction was misaligned to the standards’ intent at his grade level. Finally, Dee Mand cross-referenced depth of knowledge and used knowledge structures to address rigor. Ultimately, each educator understood the Reading Rope and how to use data to improve instruction for students.

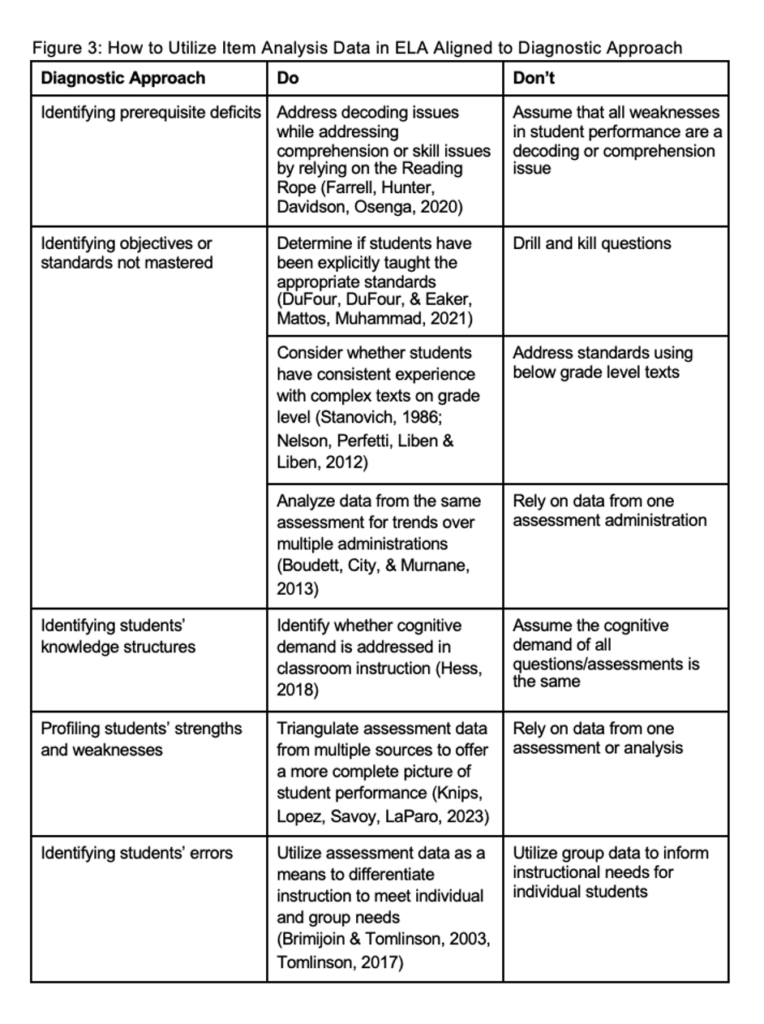

Embracing an and approach to diagnostic item analysis is an art form demanding guided practice. Such an and approach requires educators to recognize assessment should inform analysis (Salkind & Frey, 2023). Furthermore, educators should understand their context, dig into layers of data, and recognize applications and limitations of assessment results. Hence, a set of dos and don’ts in Figure 3 serves as a practical guide for navigating item analysis data in ELA instruction.

Conclusion

The tyranny of or gives way to the genius of and when educators integrate the principles of the science of reading with a diagnostic approach to assessment data analysis. By doing so, educators empower themselves to make informed decisions, tailor instruction to individual student needs, cultivate a culture of continuous improvement in ELA instruction, and increase student achievement.

Assessment results ultimately do not close reading gaps. Instead, careful, and appropriate use of assessment data can and should be leveraged to uncover why students are not meeting standards and inform the most effective instruction to close gaps and impact student achievement.

It is a research-based best practice to teach educators about the complexities involved in modern item analysis and show them how to apply it responsibly. Engaging in such a process capitalizes on teacher efficacy and enables the profession to make the best decisions for all students.

Figure 3: How to Utilize Item Analysis Data in ELA Aligned to Diagnostic Approach

Archer, A., & Hughes, C. (2011). Explicit Instruction: Effective and Efficient Teaching. New York: Guilford Publications.

Boudett, K. P., City, E.A., & Murnane, R. J. (2013). Data wise: A step-by-step guide to using assessment results to improve teaching and learning. Harvard.

Brimijoin, K. & Tomlinson, C.A. (2003). Using data to differentiate instruction. Educational Leadership 60(5). Retrieved from https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/using-data-to-differentiate-instruction

Brookhart, S. (2023). Classroom assessment essentials. ASCD.

Brookhart, S.M. & Nitko, A.J. (2019). Educational assessment of students. (8th ed.). Pearson.

Catts, H. W. (2022). Why state reading assessments are poor benchmarks of student success. The Reading League Journal 2022(Jan-Feb). Retrieved from https://www.thereadingleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/JanFeb2022-TRLJ-Article.pdf

Collins, J. (1994). Built to last: Successful habits of visionary companies. Harper Collins.

DuFour, R., DuFour, R., Eaker, R., Mattos, M., Muhammad, A. (2021). Revisiting professional learning communities at work: Providing insights for sustained, substantive school improvement. Solution Tree.

Farrell, L., Hunter, M., Davidson, M., & Osenga, T. (2020). The simple view of reading. Retrieved from https://www.readingrockets.org/article/simple-view-reading

Gareis, C.R., & Grant, L.W. (2015). Teacher-made assessments: How to connect curriculum, instruction, and student learning (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, Reading, and Reading Disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7(1), 6-10. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193258600700104

Hess, K. (2018). A local assessment toolkit to promote deeper learning: Transforming research into practice. Corwin.

Kern, A. M., & Hosp, M. K. (2018). The Status of Decoding Tests in Instructional Decision-Making. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 44(1), 32-44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534508417749874

Knips, A., Lopez, S., Savoy, M. & LaParo, K. (2023). Equity in data: A framework for what counts in schools. ASCD.

McTighe, J. (2014). Transfer goals. Retreived from https://jaymctighe.com/downloads/Long-term-Transfer-Goals.pdf

McTighe, J. & Ferrara, S. (2024). Assessment learning by design: Principles and practices for teachers and school leaders.

Mertler, C. (2007). Interpreting standardized test-scores: Strategies for data-driven instructional decision making. Sage.

Moats, L., Tolman, C., & Paulson, L.H. (2019). LETRS (3rd ed.). Voyager Sopris.

Moore, C., Garst, L.H., & Marzano, R.J. (2015). Creating and using learning targets & performance scales: How teachers make better instructional decisions. Learning Sciences International.

Nelson, J., Perfetti, C., Liben, D., & Liben, M. (2012). Measures of text difficulty: Testing their predictive value for grade levels and student performance. Council of Chief State School Officers, Washington, DC.

Ohio Department of Education (2017). Ohio’s learning standards for English Language Arts. Retrieved from https://education.ohio.gov/getattachment/Topics/Learning-in-Ohio/English-Language-Art/English-Language-Arts-Standards/ELA-Learning-Standards-2017.pdf.aspx?lang=en-US

Ohio Department of Education (2020). Ohio’s plan to raise literacy achievement. Retrieved from https://education.ohio.gov/getattachment/Topics/Learning-in-Ohio/Literacy/Ohios-Plan-to-Raise-Literacy-Achievement.pdf

Ohio Department of Education (2023). Implementing Ohio’s plan to raise literacy achievement, Grades K-5. Retrieved from https://education.ohio.gov/getattachment/Topics/Learning-in-Ohio/Literacy/Implementing-

Ohio’s-Plan-to-Raise-Literacy-Ach-1/K-5-Literacy-Implementation-Guide-2023.pdf.aspx?lang=en-US

Popham, W. J. (2020). Classroom assessment: What teachers need to know (9th ed.). Pearson.

Salkind, N. & Frey, B. (2023). Tests & measurements for people who (think they) hate tests & measurements (4th ed.). Sage.

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S. Neuman & D. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook for research in early literacy (pp. 97–110). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Shanahan, T. (2014). How and how not to prepare students for the new tests. The Reading Teacher, 68(3), 184-188.

Shanahan, T. (2024). Should we grade students on the individual reading standards? Retrieved from https://www.shanahanonliteracy.com/blog/should-we-grade-students-on-the-individual-reading-standards-1

Sharratt, L. & Fullan, M. (2022). Putting faces on the data (10th ed.). Corwin.

Shermis, M. D. & DiVesta, F. J. (2011). Classroom assessment in action. Rowman & Littlefield.

Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew Effects in Reading: Some Consequences of Individual Differences in the Acquisition of Literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21(4), 360–407. http://www.jstor.org/stable/747612

Steiner, D. M. (2023). Nation at thought: Restoring wisdom in America’s schools. Rowman & Littlefield.

Tomlinson, C.A. (2017). How to differentiate instruction in academically diverse classrooms. (3rd ed.). ASCD.

TNTP. (2018). The Opportunity Myth: What Students Can Show Us About How School Is Letting Them Down—and How to Fix It. Retrieved from https://tntp.org/tntp_the-opportunity-myth_web/

Webb, N. (2006). Research monograph number 6: Criteria for alignment of expectations and assessments on mathematics and science education. Washington, D.C.: CCSSO.