Martin County was the first of any of the larger school districts across the state of Florida to open for in-person learning this fall during the COVID-19 pandemic – a bold move during an uneasy and uncertain August in the Sunshine State.

While many other districts, including Palm Beach County to the south, opted to delay learning or start remotely, Martin County kept to its mission of starting on time, providing a sort of litmus test for how well a district could cope with the threat of coronavirus and face-to-face instruction.

During the first week or so, it was admittedly touch and go.

“In the beginning, we thought were just going to have to close a classroom if someone was sick,” says Dr. Tracey Miller, Chief Academic Officer for the district. “We thought everyone would have to go home for 14 days. But as more information became available on social distancing and spread, it became clear that students and staff would not need to go into quarantine over one case.”

Miller says that was a game-changer.

Since then, the Martin County district has made it through its fall semester successfully, providing face-to-face instruction for more than 70% of its students in a state where coronavirus numbers have been high. None of its schools have had to shut down, which is better than even during some Hurricane seasons here.

“We have been fortunate to be able to have weathered the storm without closing any schools,” Miller says. “Opening on time, that was a tremendous accomplishment. So, we’re feeling pretty good today. There’s a pretty good sense of relief right now.”

Teachers in this district of 18,000 students finished up their semester last week and are enjoying a two-week break free from thoughts about school. Miller says they’ve earned it.

“I sent a video message to teachers last night that this was the last time that they would hear from me in 2020,” Miller says. “They need a break. They need to disconnect. They need to unplug. They need to just focus on their families to take time for themselves, and to recharge to be able to do all the things that they probably haven’t been able to do.”

Making in-person a reality

Martin County’s administrators, staff and faculty serve a dozen elementary schools, five middle schools, three regional high school and three alternative schools. The student population in this A-rated district is diverse, with a growing Hispanic and English language learning base and 52% qualifying for free-and-reduced meals. It provides a range of services, from those in pre-K to those students with disabilities. The district stretches to serve wealthy families along the Treasure Coast to a much less-affluent populace in the more remote Indiantown to the west.

Providing an education to such an expansive area and a range of schools could have presented big challenges for Martin County when the first shutdown occurred on that fateful Friday the 13th in March. Spring break only gave district officials one week to scramble to get remote learning off the ground.

One of the key components already in place was a 1:1 device initiative for all high school students. Over the rest of the week, it managed to get devices into the hands of other students through pickup programs at several school locations, along with hot spots for those who needed them.

One of the key components already in place was a 1:1 device initiative for all high school students. Over the rest of the week, it managed to get devices into the hands of other students through pickup programs at several school locations, along with hot spots for those who needed them.

“When you talk about turning on a dime, we literally did that,” Miller says.

That Monday, schools reopened but not in person because of a state mandate. They remained that way for the rest of the semester, operating essentially asynchronously using Google Classroom and Zoom.

“We were all kind of huddled up in our houses,” Miller says. “We definitely learned what Zoom fatigue is. We definitely learned how to communicate through online platforms. I started sending video messages to the teachers to communicate what was happening and any changes or updates or training that we had available.”

Martin County, ever the trend-setters, did not go quietly into the summer, opting to host in-person graduation ceremonies in July at a time when very few gatherings were happening.

In addition to handing out thousands of meals, its technologists were still deploying and fixing laptops. And as the county started to slowly reopen and the possibility became real that students would be welcomed back in person, the risk management team was collaborating on safety measures for the fall. On the academic side, a synchronous hybrid instruction model was being forged, even though the majority of students would be in person.

“Probably the most important component for us was ensuring that our students, regardless of what their personal circumstances were, would have access to the same high quality teachers, high quality curriculum and high quality instruction that they’ve always had,” Miller says. “Choosing a synchronous model would enable our students to not miss instruction because of the virus.”

By opening in person, it provided a wealth of other benefits.

“Families experienced lots of struggles and hardships because schools weren’t open,” she says. “So, when we opened back up, that really allowed the community to open up and the economy to open up. I don’t know that everyone’s really made the connection: We are providing that safe, nurturing environment with people that they know and who care about them, along with the social-emotional aspect. It’s a piece of educating the whole child. We really came to understand what that means.”

Staying open during the fall

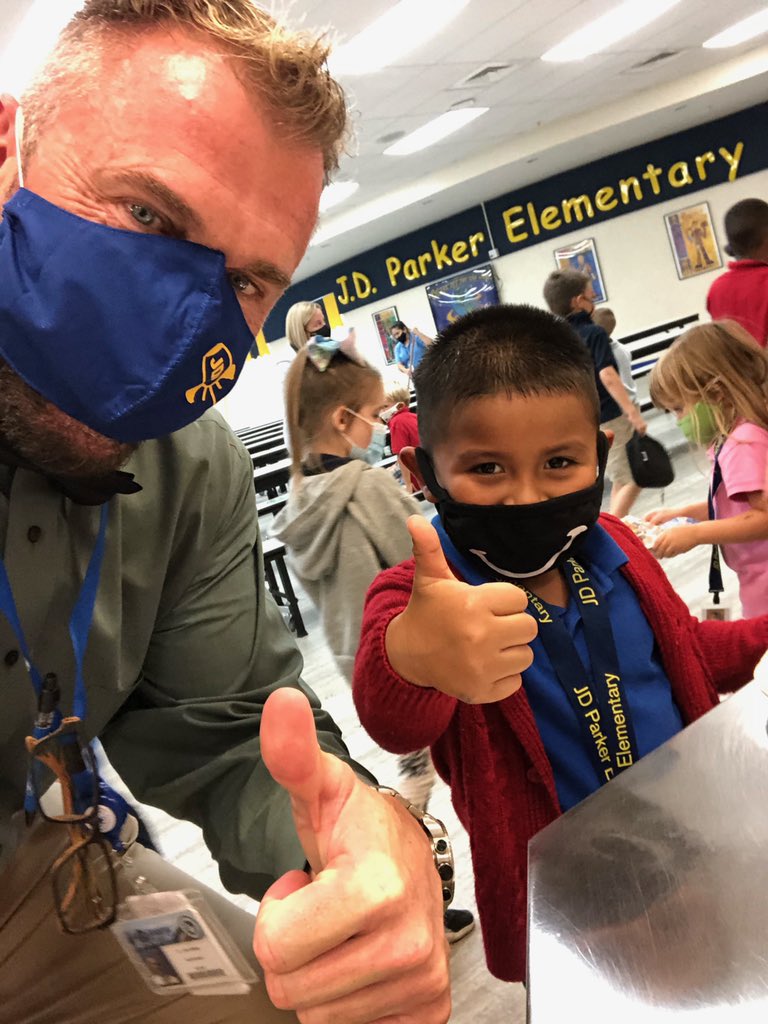

Martin County opened its schools on Aug. 11 with robust safety measures put in place led by their “Quaranteam” – a group that consists of county health department officials, district staff and school staff. For all cases that arose, they would “surgically” contact-trace where that child was by looking at seating charts, bus charts, student activities, lunch schedules, where they sat at lunch and who they were with.

“We didn’t want to send kids home unnecessarily,” Miller says. “We didn’t want to send people back into quarantine.”

So, they pressed on while others weighed their options.

So, they pressed on while others weighed their options.

“Everyone was watching us to see how it was going to go,” Miller says. “I really believe our surrounding districts were looking to see if we were going to have to close schools within the first couple days – somebody’s going to get sick, or we’re going to be the super spreaders that schools were predicted to be. We quickly found out that wasn’t the case.”

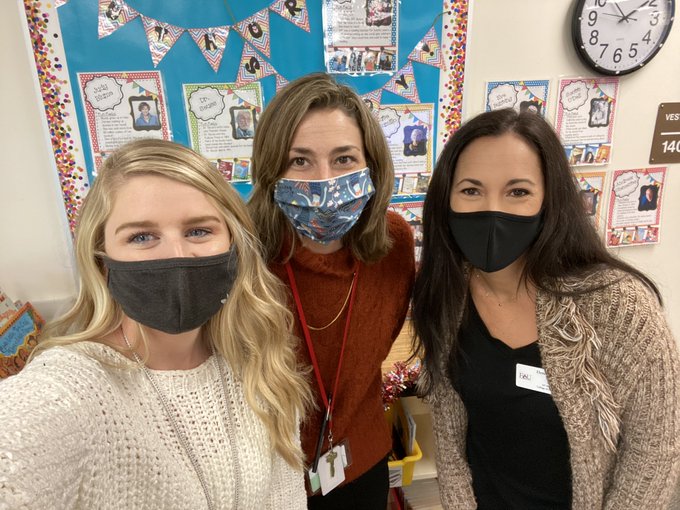

Instead, no schools have been shuttered because of coronavirus. Teachers and staff levels have remained strong. Miller says safety protocols were key to staying open, and experiences made the transition to in-person possible.

“We’re still very vigilant. We still follow the CDC guidelines, wear our masks, wash our hands often and sanitize,” she says. “We have extra cleaning, one-way hallways, all of that. But I think the feeling is a little better. We feel a little more at ease, a little more normal and a little bit more like school. The pandemic isn’t constantly in front of our minds all day. It’s something that’s always running in the background.”

Because of that, Martin County has been able to focus more on instruction and the services it typically provides.

“Our mission is to educate all students for success, and we never lost sight of that,” Miller says. “I think that’s what brought our team together, is understanding our role not just for our students, but really understanding our role as part of the greater community, and how education really is the backbone of the economy and the community here.”

Heading to the break with some momentum

Miller says the district is doing what the Florida Department of Education hoped it would – provide a panopoly of services, from academics to afterschool care. Admittedly, they look “a little different under the pandemic,” but it’s hard to argue with the results. In addition to in-person learning, Martin County has been able to conduct athletics and hold concerts to go along with those graduations.

“The kids have never been so happy to come back to school,” Miller says. “It hasn’t been easy, that’s for sure.”

There have been immense challenges, starting with the exhaustive safety requirements, measuring out desks and being vigilant on mask wearing and social distancing. Volunteers still haven’t been allowed back in schools, and there are still no field trips.

There have been immense challenges, starting with the exhaustive safety requirements, measuring out desks and being vigilant on mask wearing and social distancing. Volunteers still haven’t been allowed back in schools, and there are still no field trips.

And the hybrid model isn’t best instructional option for the district. It is very tough on teachers and it isn’t the same for those students at home.

Though the number of learners continue to trend more toward in-person learning than remote, a little less than 25% will be operating virtually in January. Martin County continues to make that accommodation for all students but says average grades are better among those who are in class (80.5%) compared with those remote (78.3), and there are far fewer Fs among those taking part in person.

“That’s only a two-point difference,” Miller says of the grade-point gap for middle and high school students. “But that’s the difference between a B and a C. For some, it’s been a beautiful model, but the data that says on average students who are remote learners at home, their overall average grade average is less than students who are in person.”

On Dec. 1, a new executive order from the state allows districts to require asking students who are struggling to come back to schools to learn in person. Martin County has been talking throughout the semester to families to discuss student progress to try to mitigate any potential issues. A waiver option is still there for parents whose children are struggling, but their children run the risk of potentially being retained or not graduating on time. For those students, Miller says, the in-person environment could save their academic years.

“If they’re not being successful, then the ask is that they come back to school where we can provide additional supports and better meet their needs inside the classroom in our buildings,” Miller says. “We’re being real honest with parents to let them know the risks associated with not coming back to school for those students who haven’t been successful.”

As academic success is the focus of the district, it wants to do everything it can to help those students achieve.

“We want everybody back who can be here,” Miller says. “That’s clearly our message. Teachers would like their kids back as well.”