With so many aspects of K-12 education becoming politicized, Superintendent Walter “Rick” Clemons sought direct input from the Gloucester County Schools community. School board meetings provide a public comment period for residents to express opinions, but they are not generally a back-and-forth forum.

Clemons, Virginia’s 2023 superintendent of the year, held an open house at which district leaders and school board members answered parents’ and other community members’ questions about a range of hot-button topics, such as critical race theory and whether the concept is being taught in Gloucester County Schools. School health policies, the impact of social media and curriculum were also discussed, Clemons said.

“Whether they have kids in the school system or whether they don’t, people want to feel you’re able to talk to them and that nothing is being held in secrecy,” Clemons says. “We have this avenue where we’re able to talk about issues, and it has mitigated a lot of the dissension we’re seeing around the country.”

Clemons’ commitment to transparency is an example of how District Administration’s latest three superintendents to watch are steering their schools toward continuous improvement.

Prioritizing public service

Another popular community event in Gloucester County Schools is the series of Dads’ All Pro Breakfasts, which have recently been attended by about 200 families. The breakfasts had been put on hold during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. “It’s encouraging to see the dads come out and be a part of their kids’ lives,” Clemons says. “We want to continue to facilitate that and do all we can to be a place of service.”

In the classroom, Gloucester County’s educators are still navigating the impacts of the pandemic, particularly when it comes to learning lost by the district’s youngest and most vulnerable students. However, students didn’t fall as far behind as they might have had Clemons and his team not led a phased return to in-person learning in the fall of 2020, he says.

The first to return were the youngest children and students with more severe disabilities. Educators’ and families’ confidence in in-person learning grew with each group of students that came back. Everyone was back in-person, on a hybrid schedule, by November 2020, and the district returned to its regular schedule in 21-22. “We still have work to do to get back to pre-pandemic levels,” Clemons says. “But the way we were able to navigate the pandemic paid off with some growth and proficiency that our kids made this past cycle. I attribute that to having a solid framework for being back at school and a greater sense of normalcy during the previous year.”

Superintendents Summit

The District Administration Superintendents Summit offers cutting-edge professional development to school district superintendents and other senior education executives to inspire innovation and leadership excellence in K-12 education. Upcoming events in this series:

Nov 9 – Nov 11: Omni La Costa Resort & Spa, Carlsbad, CA

Dec 14 – Dec 16: Ponte Vedra Inn & Club, Ponte Vedra, FL

Prior to Clemons’ arrival nine years ago, the district did not have a strategic plan and two of its schools, including its only high school, lacked accreditation. Clemons spearheaded the development of a comprehensive plan anchored by community engagement and communication, efficiency of operations, and social-emotional wellness and mental health care. The plan is updated annually.

All of Gloucester County’s schools are now accredited, and the focus has shifted to making long-needed capital improvements. The district persuaded the state’s legislature to allow it to use a one-cent sales tax to fund construction, including a major renovation of the high school that is just getting underway. It’s this high level of continuous improvement that Clemons says drives his leadership philosophy.

He and his team are focused on enhancing personalized learning to meet the needs of every student, supporting families and keeping the community informed, as well as ensuring the district is a place at which teachers and staff are enthusiastic to work. “It’s about never being satisfied where you are,” he concludes. “We have had a lot of success and we have a lot of things to be proud of. But there are a lot of things that still need to be done.”

Telling stories of continuous school improvement

To be successful at continuous school improvement, superintendents have to view the profession as “more than a job.” They should also try to hire teachers, paraprofessionals, bus drivers and other staff members who feel the same way, says Superintendent Robert Fulton of the Cape Henlopen School District in Delaware. “We try to attract and keep people who have that mindset—people who want to be here and want to help,” says Fulton, Delaware’s superintendent of the year.

He also works to engage staff in decision-making so they can spread their enthusiasm to the community. As superintendent, he tries to be visible “in every part of the district.” “If we aren’t telling our story and sharing our challenges and successes, who’s going to?” he asks. “I want staff to know what’s going on so they know what to say when people ask them what’s happening at their school.”

One of the challenges—enrollment growth—is one most district leaders wouldn’t mind confronting. It is also rare for a district in the mid-Atlantic and Northeastern U.S. Fulton says families were drawn to the community by his team’s ability to offer in-person learning early in the pandemic. This was a huge help to parents who weren’t able to work from home, he adds. “The academic growth of our students during the last two years wasn’t what it would normally be, but it was really good compared to other districts,” Fulton explains.

More from DA: Why these 11 schools top the latest rankings of America’s healthiest

The district’s enrollment was less than 5,000 in 2012 but is now growing beyond 6,300. Three tax referendums passed since 2014 have allowed the district to build new schools and renovate several others. Cape Henlopen also operates a school for students on the autism spectrum that serves the entire county. “Those specialty populations are a big part of who we are,” he adds.

Two of Cape Henlopen’s kindergarten classes are part of the Spanish immersion program, which has 1,300 students enrolled and a waiting list. The goal is for students to become bilingual by middle school and then begin learning a third language in high school. The overall mission for 2022-23 is continuous school improvement by getting back to a regular in-person routine and recovering from COVID’s emotional toll. “The interaction between everybody needs to get back to normal,” Fulton says. “I need to be talking to kids, visiting community groups, and communicating, connecting and developing relationships.”

One key source of support is Delaware’s 18 other superintendents, who, because the state is so small, are able to meet regularly with each other, the governor and the state’s secretary of education and other political leaders. “People know each other and talk frequently,” he explains. “Especially when you’re going through challenging times, you can make change, and change can occur quickly.”

Room to experiment

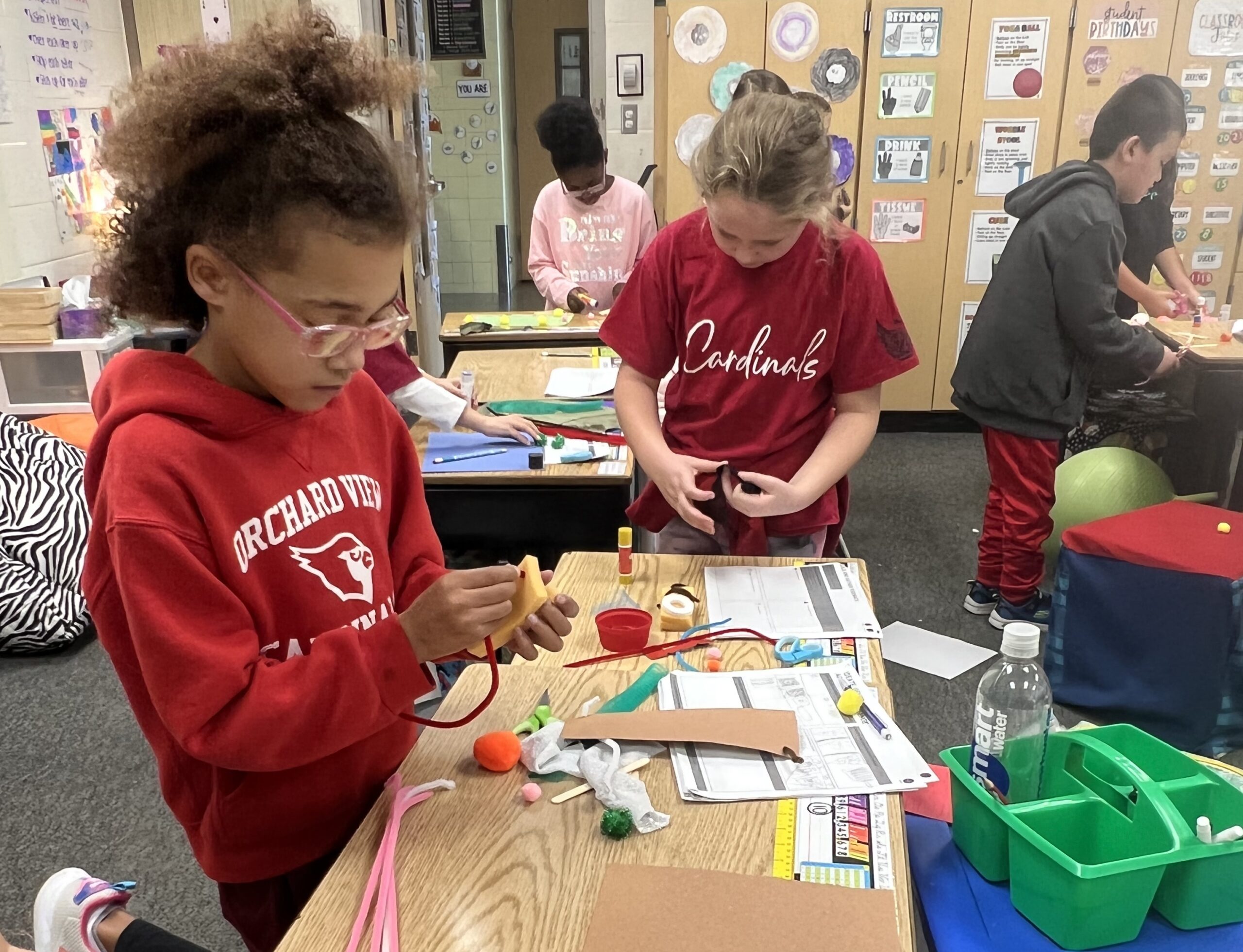

Superintendent Jim Nielsen first walked through the doors of Orchard View Schools in 1970, when he was 5 years old. “I’ve lived here my whole life,” Nielsen says of the small school system in Muskegon, Mich. “My journey has been about loyalty and commitment to this district, and I feel that the district has shown the same to me.”

Nielsen’s commitment to continuous school improvement is evident in the personalized learning academy that came into its own as the district’s vehicle for virtual instruction during the pandemic. The academy is now geared toward students in grades six through 12 who have struggled with more traditional instruction and need a greater degree of support from educators. Hybrid classes are another way the district is trying to meet the diverse needs of students, some of whom don’t want to attend school in person full-time but who want to participate in athletics and other extra-curricular activities.

Orchard View also operates the Innovative Learning Center, a regional adult education program that is organized around project-based learning and focuses on helping residents upskill and make connections with employers. The center, which could serve up to 200 students this school year, also offers daycare, access to public health providers and pathways to a local community college.

Nielsen and his team also have prioritized STEAM and career and technical education in elementary and middle school. Middle school students have the opportunity to participate in after-school welding, aviation and other activities at the district’s CTE center. On the social-emotional side, Nielsen is working to put more mental health clinicians in his schools and embed an equity mindset throughout his district. “We have been very inclusive of students of all backgrounds, beliefs, races and sexual orientations,” he points out. “Diversity is the one thing we all have in common.”

As for the challenges ahead, Nielsen cites one overwhelming issue, “The concern that we have now, have had and will have, is staffing,” he says. “If you were to ask me my 15 biggest concerns, 12 of them are staff-related. It’s not because our staff is not doing a great job, it’s because we just can’t find the people.”

Still, Nielsen is adamant that a district’s success goes way beyond the superintendent. “The idea of ‘superintendents to watch’ makes me a little uncomfortable,” he concludes. “I have a great team of administrators, professional staff and support staff. And we couldn’t do the stuff we’re doing if not for a board that’s supportive, that allows us to experiment, that says ‘How can we help you make that happen?'”