February 3, 2020, started out like any other day for our district in York County, VA. The school day had ended, and things were winding down when the call came in. A serious electrical fire had caused a catastrophic failure in the main electrical distribution panel that served both a middle and high school.

Thankfully, no one was hurt, but once all the data was collected it became clear that we were dealing with major decisions to be made on two fronts – how to clean and restore the multi-school complex building and how to continue the education of 2000+ students without that building for the next two months. Fortunately, we had built an agile leadership team that was ready to take on the challenge with confidence and clarity.

Read: Updated: 314 free K-12 resources during coronavirus pandemic

Building the team

Good leaders are charged with making good decisions. It is tempting to rely on prior experience and expertise, but many decisions require something more —careful consideration, data, collaboration, clarity and targeted communication. Decisions in times of crisis have another layer of urgency and complexity – they are often controversial, emotionally-charged, and can have far-reaching impact. These decisions are tougher to make and implement, requiring communication to stakeholders before, during, and after. This past year our district met a series of very serious challenges that required timely, transparent, and rational decision making literally in the face of fire and pandemic.

Complex decision making in schools

As with any leadership team, we are often working through multiple complex decisions simultaneously in the course of a normal school year. Our year started out with what felt like large and complex decisions, including: changes to the primary grading scale, midterm exam expectations for high school courses, potential school calendar start day adjustments, changes to elementary recess expectations, and expansion of special education classrooms and staffing. These distinct issues required the collaborative efforts of leaders from Instruction, Student Services, Operations, School Administration, Information Technology, Finance, Human Resources and Public Relations. Compared to what was to come, however, these earlier decisions now seem relatively simple.

Read: Creativity in Crisis: How to teach hands-on engineering remotely

Getting the right people in the right places

Determining who should have a seat at the table in decision making is the first and perhaps the most important decision you will make to ensure successful implementation and satisfactory problem resolution. It starts with having the right people at the ready as a result of finding and hiring the highest quality educators and administrators. You then must give them the tools, trust, opportunities, and support to practice flexing their decision-making muscles all along the way.

I am especially proud that the decision-making protocols that we use wholly, or in part, on every decision in our district are embedded in our hiring practices. We have had several executive and school leadership openings with the good fortune of having multiple internal and external potential candidate applicants. Using a decision-making strategy helped us stay focused on our mission-based criteria, and removed actual or perceived bias from the equation. We left the hiring process confident that we had chosen the best candidates to meet our organizational needs and priorities.

Read: In-person or remote learning? Let each family decide.

Giving them the right tools

As a district, we work deliberately to build our leaders’ capacity for strategic decision making. Our goal is to maintain clarity, improve our ability to frame the decisions, and clearly communicate around the work being done. We have provided our leaders with job-embedded professional development from TregoED, a nonprofit that works to build the capabilities of school leaders using research-based problem solving and decision-making tools. These tools give us a common road map and language to work through complex decisions. Each stakeholder may come to the table with different ideas, different skill sets, and different priorities, which are essential pieces of the pie. To ensure that these tools become part of our daily routines, I expect our team to use this common approach to work together and communicate progress on all major decisions going forward.

Include necessary stakeholders

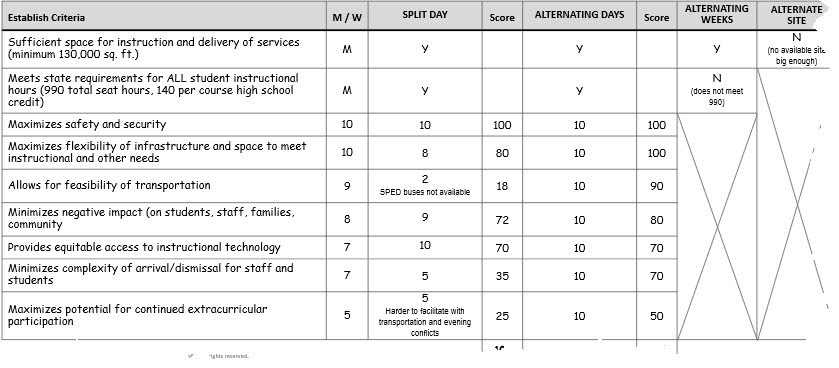

Using a step-by-step process for decision making like TregoED’s Decision Analysis, essentially puts a framework around our decisions. Our team has the confidence and parameters for including appropriate stakeholders in decisions made in our day to day work. For example, recent decisions made by our special education committee included input from the director, building administrators, coordinators, and teachers.

Business and school partnership decisions included local business owners, the county economic development staff and YCSD senior leadership. Parents have been included in many district decisions including those around the school calendar and transportation challenges. Including various groups of stakeholders, especially those who may hold differing viewpoints, can be worrisome but it is essential for ensuring a high-quality solution.

Read: Why school districts aren’t asking for all of their laptops back

Moving the academic needle

Perhaps the most exciting results we have had from these cumulative decisions have been those that improved student learning. We have seen a narrowing of a reading performance gap to its lowest level since 2011 and have developed a three-year plan to improve outcomes for students with disabilities. Our approaches have allowed us to address unexpected results or trends on such critical topics as the disproportional representation of student subgroups in discipline referrals and absenteeism, and a drop in one school’s grade level reading scores. Using similar process tools, we have been able to proactively implement change to address and prevent potential problems rather than reacting to problems as they arise.

Crisis # 1 – The Fire

While using Decision Analysis gave us confidence that we were not only doing good work and that our decisions were sound, we did not yet fully appreciate how critical the questioning techniques and framework for decision making would be in times of crisis. The fire in our newly refurbished Grafton Complex presented, what at the time, was the greatest challenge in most of our leadership careers. Once news of the fire hit, we quickly learned that the repair process would be extensive and lengthy and that a significant portion of the building was contaminated with soot and ash.

It became apparent that we needed to come up with a plan for continuing the education of an entire middle and high school student population for at least two months – and possibly the remainder of the school year – and cleaning the contaminated building. Fortunately, with strong decision-making practices in place and the right people on the job, we were able to develop, communicate, and implement a plan that had students back in school within one week’s time. One of our Board of County Supervisors, Tom Shepperd, said: In times of crisis, you need people who have analytical thinking capabilities and you don’t get that overnight.

Read: Here are the key questions to ask to safely reopen schools

We were built for this

By having the right people in place with these decision-making capabilities and the confidence gained by embedding them in our routine practices, we were essentially built for this crisis. With our tools in place, we had built a climate and culture that empowered the people in the room to participate and speak with an equal voice. With that personal power (versus positional power) we were able to have the hard conversations.

Neil Morgan, York County Administrator, affirmed that the collaborative process allowed us to deal with conflict in a healthy way. While both the School Board and County Board of Supervisors knew we had decision-making protocols in place, they did not come to fully appreciate the importance of having those capabilities until we were all faced with a large scale, time-dependent, and highly emotional crisis. School Board Chair Jim Richardson felt that public forums and large-scale meetings were far less daunting when we were confident that the leadership team had thought of everything before making their recommendations.

Communication systems are key

Communication is an essential part of our operations to ensure we provide transparency and develop trust and understanding with our constituents. Having a team that used a common set of systematic questions and a common language in their approach made getting a clear and concise message to our community much easier. As Heather Young, principal of the middle school which would be affected by the plans to move a second school into their building on a rotating schedule, stated, DA really structured us, helping us to focus on and identify our priorities together. This allowed for a healthy discourse as we advocated for the interests of our students and staff.

We might not all have agreed with the decisions moving forward, but we all knew they were vetted, that our perspectives were heard, and the best possible choices were made. You could feel the anxiety of the 700-800 parents and participants at our public forums diminish as plans were unfolded revealing a deliberate process and the options that were considered. County Administrator Neil Morgan concurred, saying, The processes allowed us to communicate and coordinate all different facets of the county, the fire department, schools, elected officials, etc. We already had a healthy dynamic of communication and trust to work through this. At the time, this seemed like the worst thing that could ever happen, then COVID-19 came and it was only the second worse thing.

Case # 2: COVID-19

As we worked to put out the fires that resulted from having to relocate two buildings worth of students, we began to hear reports that schools were closing due to COVID-19. It looked like our tools and training were going to continue to be put to the test.

It turns out though, that we were actually at a bit of an advantage over neighboring districts because of the recent fire crisis. We had a head start on supporting students outside of a normal school setting as we had already begun incorporating virtual learning and online teacher support in our plans to supplement students’ reduced access to physical buildings. In addition, we had been using the decision-making processes so much recently that they were now becoming second nature. Thirdly, we had a strong communication system in place. Our decision-making processes provided us with a framework of strong talking points around the criteria that were used and all the alternatives that were presented. So, when someone asked us, did you consider¦, we could say that we did and provide documentation as to why it was not the best solution for us.

The questions involved in the Decision Analysis protocols also provided us with a way to make sure that any new ideas and alternatives brought to us had been vetted through the process. When a colleague had a good idea – we used the same process questions to determine the risks. We all understood that the ideas were not being criticized but rather were being protected by thinking through all the possible problems that could occur.

Communication systems in place

When we were hit with the challenge of closing all schools, we already had strong communication channels in place including an askYCSD@ycsd.york.va.us account set up to collect questions and website FAQ’s to address them. Not all communication systems we used in the fire worked with the COVID-19 crisis – for example, the successful community forums were no longer possible!

Katherine Goff, public relations and communications officer in our district, helped us adjust communications accordingly. She stressed that many of the practices we established were still viable. We needed to make sure that the elephant was being served only one piece at a time- so as not to overwhelm people and to provide a clear and consistent message that pertained to their concerns. In our public forums after the fire, we were able to frame and communicate our talking points to hit the pre-collected questions before people came to the mic – making the conversations less confrontational. Information and questions brought up in the onslaught of social media were quickly resolved by community members who had the facts on how alternatives were either selected or rejected.

For both crises, the visible, transparent process used to determine our course of action was always front and center. Dr. Jim Carroll, chief operations officer, whose job put him in the forefront during both crises, believed that the advantage of having these question-driven processes is that individuals came prepared with well thought out ideas and options which added to the efficiency of our organization. My experience has been that the longer and harder you are beating at something the more emotional it can get- without a structure to follow, people go down rabbit holes, expanding the time needed and resulting in bad decision making. When time was of the essence both after the fire and when COVID-19 hit our schools, we were able to approach problems with familiar tools and relative calm. We were able to ask the right questions to get the job done quickly and with confidence.

Read: How schools can improve CTE during COVID-19

Lessons learned:

Some of the many lessons we have learned in the process of making decisions with clarity and confidence include:

Start with the right people: Using a rigorous hiring process and giving those people the tools that they need to succeed can help you get through any crisis with confidence that you are taking the best possible actions for your district.

Use a collaborative approach: Determining which stakeholders need to be in the room for each decision made can be very important. Using process as the norm for our decision making provides a common language, experience, and results across departments. With the increased confidence in our approach and execution comes an increased willingness to collaborate with community and stakeholders.

Use a good decision-making process: When you have embedded critical thinking questions in your decision making, you can have those courageous and sometimes difficult conversations that will result in more viable solutions.

Be flexible: You do not always have to follow the entire process start to finish to get good results. You can make the processes your own and adapt them to the situation at hand. Using bits and pieces of a good process can help you get a handle on the situation you are facing.

Communicate with clarity: Decisions that are protected by data and a collaborative, defensible approach, are more easily communicated, championed, and supported. We are better able to explain our choices and actions and this clarity gives leaders the confidence to move forward in bold, new ways. Particularly in crisis situations, the framework can help diffuse emotions and keep rumors at bay.

The bottom line is having a staff with great decision-making capabilities can help you do extraordinary things throughout any school year. We have seen positive results in academics, facilities, budgeting, and other areas. Those same capabilities can determine success or failure in times of crisis when time is of the essence. Our ability to get students back to class after the fire and then quickly pivot to home instruction when the pandemic hit, was a credit to our team’s skills and confidence.

Victor Shandor, Ed.D. is superintendent of the York County School Division in Yorktown, Va.

DA’s coronavirus page offers complete coverage of the impacts on K-12.