“Equity grading is not leveling the playing field… It is simply lowering standards so that school districts look like they are meeting kids where they are, when in fact they are hiding their failures behind ‘equitable’ policies.”

That’s how one teacher summed up the impact of the “equitable” grading mandates that have swept districts and schools in the post-pandemic era.

For our recent report, “’Equitable; Grading Through the Eyes of Teachers,” my co-author, Adam Tyner, and I surveyed nearly 1,000 teachers across the country. More than half say their school or district has adopted at least one “equitable” grading policy. For example:

- 31% must allow unlimited retakes

- 29% cannot give late penalties

- 27% cannot assign a grade of zero, even for work that isn’t completed or submitted.

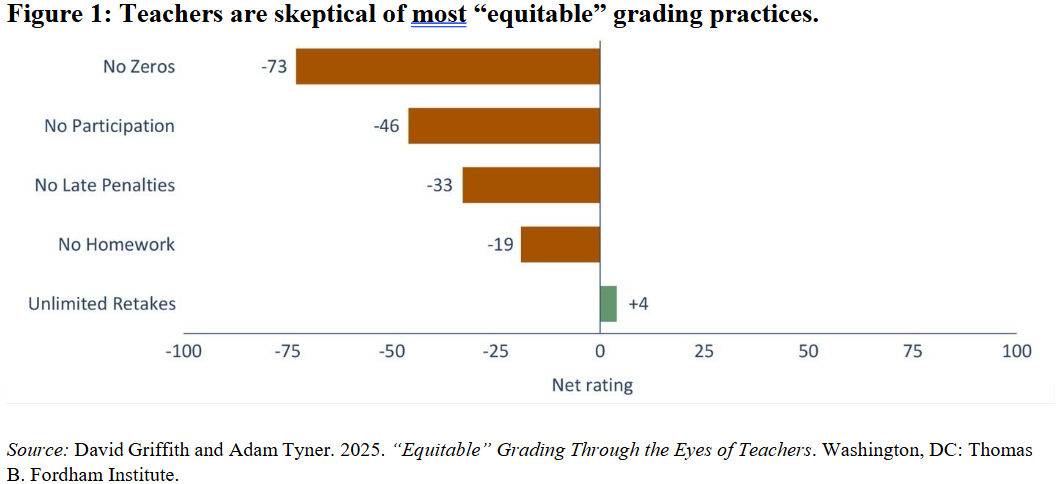

At least four of the five practices that we asked about are unpopular with teachers. For example, nearly three-quarters of teachers say “no zeros” is harmful to academic engagement, while just one in 10 say it is helpful.

In fact, the only “equitable” grading policy with a positive rating is “unlimited retakes”—and even here, many teachers are skeptical.

Collectively, these results—and the unprecedented grade inflation that has accompanied the rise of equitable grading—suggest it’s time for policymakers to stop indulging this fad, press the reset button, and return to the core principles at the foundation of most K12 education systems.

Principle 1: Keep expectations high

Research confirms what common sense suggests: that higher expectations produce better outcomes. One Florida study found that elementary students assigned to tougher-grading teachers made more progress in reading and math.

An analysis of North Carolina data found that students of high school math teachers who graded strictly also did better in subsequent math courses. Conversely, lower expectations produce worse outcomes.

For example, when North Carolina mandated lower cut scores for letter grades in 2014, low-performing students’ attendance declined. All of which makes it troubling that “equitable” grading policies—which effectively lower grading standards—are more prevalent in “majority-minority” schools (i.e., schools where the majority isn’t white).

Simply put, the low expectations embedded in these policies are harming the students whom their proponents claim they help. That’s not equity. It’s a not-so-subtle form of neglect.

Principle 2: Respect teachers’ judgment

One size doesn’t fit all. After all, each school, subject, assignment, grade level, teacher and student is different.

So, it’s absurd to suggest that a single, districtwide rule should govern both a ninth-grade remedial math quiz and a twelfth-grade honors civics essay—particularly when that rule isn’t grounded in solid research—or that every teacher should take an identical approach to retakes, homework, or participation.

Some version of that principle also extends to individual students, whose treatment neither can nor should be perfectly equal. After all, a good teacher knows when to extend grace to a student who is experiencing personal challenges and when to hold firm to help that same student build habits of responsibility.

But of course, no teacher can hope to strike the right balance if he or she must apply lax policies universally.

When teachers can use their judgment, they can tailor instruction, feedback and support to meet students’ diverse needs (and when they can’t, research suggests they are more likely to leave the profession). So, let’s respect their judgment instead of trampling on it.

Principle 3: Don’t reinvent the wheel

There is nothing inherently wrong with the traditional 100-point grading scale. If district or school leaders witness problematic practices, like teachers doling out extra credit on an arbitrary basis, those issues can be addressed without overhauling the entire system.

And switching to a new scale is likely to create confusion for educators, students and their families, increasing the risk of miscommunication without producing more learning.

There is also nothing inherently wrong with using points to hold students accountable. Yes, we want to develop kids’ intrinsic motivation. But not every child is going to be intrinsically motivated to push themselves on every task.

Deducting points for late submissions can discourage kids from falling behind. Withholding them until an assignment is completed is common sense.

When students get the wrong message

For as long as grades have existed, compassionate teachers have offered flexibility and grace to students facing extenuating circumstances. But when districts or schools mandate such practices, regardless of the context, students get the wrong message and teachers lose their ability to hold them accountable.

Equity grading advocates insist that their favored practices don’t do these things. But teachers’ testimony indicates otherwise. Which is why it’s time for policymakers to admit their mistake—and reverse course.

Simply put, real equity isn’t about lowering the bar. Nor is it about papering over differences to make things look “fair.” It’s about helping all students to reach their potential—something that is impossible if our education policies preclude any semblance of challenge.

Department of Education: McMahon says the shutdown had no impact on K12