When will schools reopen? Will they reopen? Will students wear masks?

How will kindergarteners keep social distance?

There are still more questions than answers about what education will look like this school year, or – for that matter – what it should look like. That uncertainty is forcing districts to be more deliberative, more transparent, and more inclusive about reopening or risk educators and families not returning.

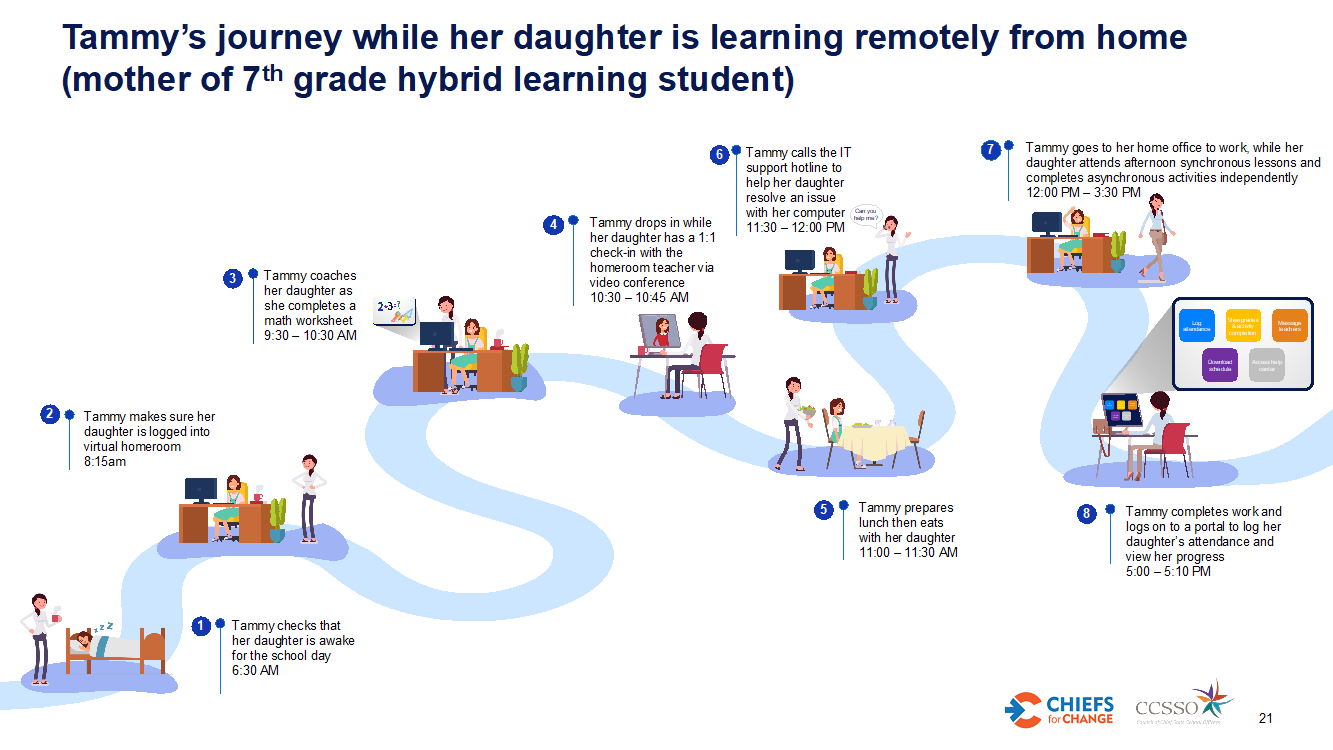

Over the last several months, Chiefs for Change – a nonprofit, bipartisan network of diverse state and district education chiefs dedicated to preparing all students for today’s world and tomorrow’s through deeply committed leadership – has partnered with the Council of Chief State School Officers and McKinsey & Company to support and assist district leaders to better understand the challenges of the COVID-19 crisis and focus on reopening. Through this work, we are supporting district leaders and school boards to pressure test their plans by simulating a day in a life of a student, a teacher, principals, and school staff, as well as a working parent/guardian.

(Click to enlarge the images below, then click your browser’s Back button to continue reading)

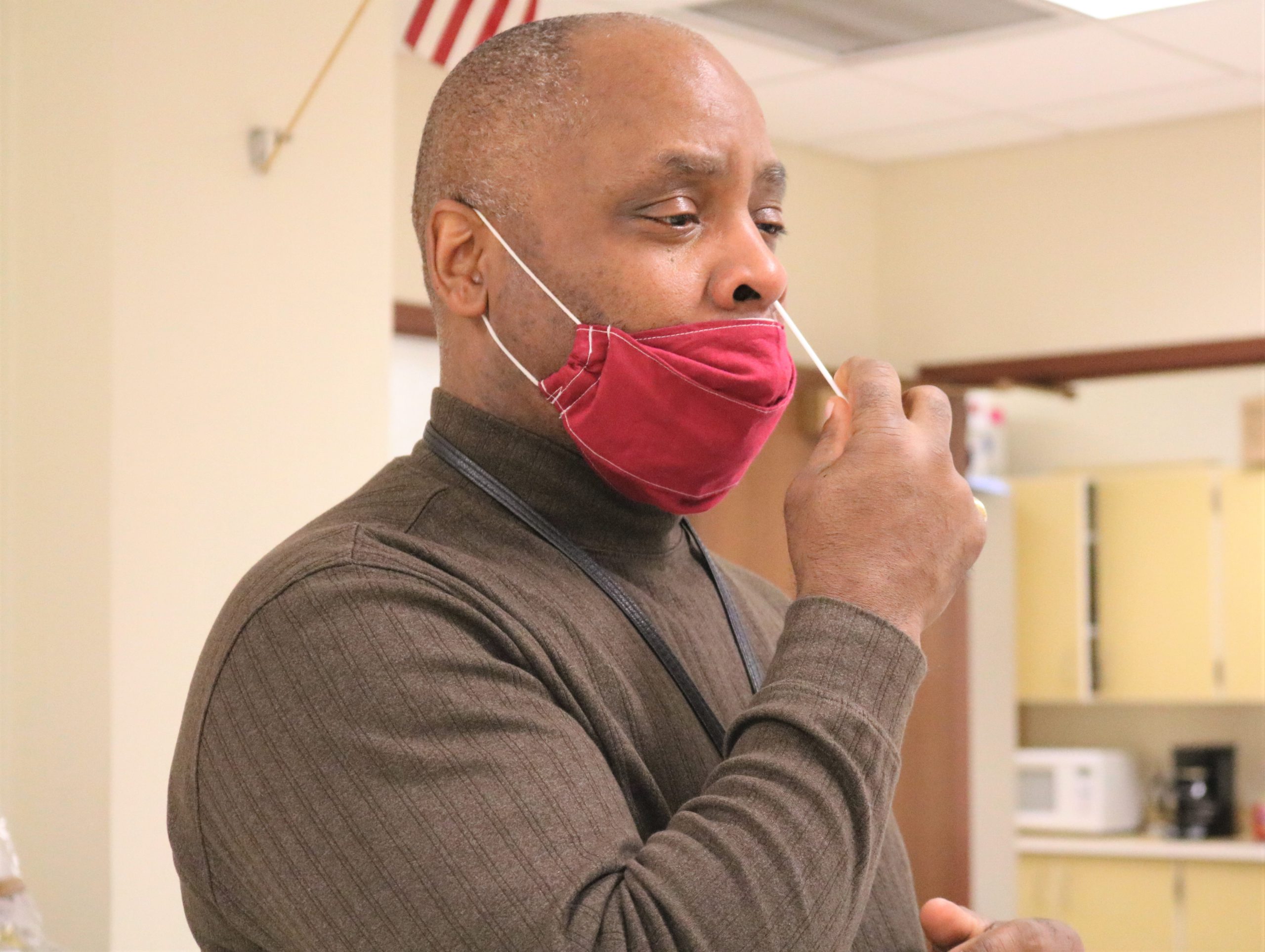

On the surface, the day in the life of a typical student is rather simple. Take the example of Malik, a fourth-grader attending a district that’s employed a hybrid model. Malik goes to school in-person on Mondays and Thursdays and learns remotely Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. On an in-person day, Malik gets on the school bus at 7:15 a.m., arrives at school for breakfast by 7:35 a.m., is in class by 8:15 a.m., with lunch at 11:30 a.m., recess at noon, and dismissal at 2 p.m.

Amid a pandemic, though, each of these events sets of a chain of questions districts must consider.

How does Malik board the bus?

Is he masked?

How full is the bus?

Those answers can be relatively easy: Single-file boarding with social distance. Mask-required. One-third full.

But they quickly become complicated, even by benign and simple challenges.

What if Malik shows up to the bus stop with his older brother on a day Malik’s class is scheduled to be remote? Does the bus driver let him board? Is it the bus driver’s duty and responsibility to know each child’s schedule? If it is, does she leave Malik alone at the bus stop or bring him to school anyway? Considering these “what if” micro-scenarios can help district leaders and their teams prepare for the alternate scenarios students and others may face.

Malik hasn’t even left the bus stop, and it’s clear that the “typical” journey to school can’t even begin without recognizing that reopening plans must include input and scenario planning from multiple teams and disciplines, including human resources, health and safety, and facilities.

Districts cannot responsibly reopen schools without pressure testing their reopening plans and taking an objective look at the gaps which will undoubtedly exist in even the best-intentioned and best laid out plans. The surest way to identify and plan contingencies for those gaps is working through day-in-the-life simulations (also known as DILO simulations) for multiple student experiences. And while we should all demand that districts develop reopening plans with students’ best interests at the forefront, we cannot ignore the other journeys that impact learning and reopening, including those of educators, cafeteria workers, bus drivers, parents, and others.

Many districts – including nearly all of the districts our members lead and whom we are supporting – started planning reopening options just weeks after schools first closed. Districts are now weeks away from the start of a new school year and many face pressure to provide scenario options that account for multiple options for learning. Reopening without making an operational investment of time to conduct in day-in-the-life simulations puts districts at risk of missing potential gaps or, worse, developing plans that unwittingly harm districts’ ability to teach and support students.

No plan is going to predict every possible scenario with perfect precision, and districts will run into challenges. But organizational leaders have an obligation to build muscle memory within their organizations – through repetition and practice – that can flex to meet the demands of any challenge.

Running any comprehensive day-in-the-life simulation requires multiple team members and coordination across multiple workstreams. In our work with districts, we have found that it takes a core leadership team to serve as the “nerve center” and to lead the process, gather data, and map each journey through reopening. And while specific workstreams will vary district-to-district, we recommend that this leadership team have input and participation from every available workstream, including, among others:

- academic calendar

- academics

- technology

- nutritional and student support

- athletics

- transportation

- health, safety, and security

- human resources

- facilities and operations

- communications and partnerships

Within a week or two of launching this process, districts should complete the analysis and map the “typical” journey of several personas. Those simulations should consider students, teachers, staff, and parents facing a variety of reopening models, including hybrid scenarios, fully-remote, and fully-in person. In addition, as an immediate next step, principal supervisors should work with principals to complete a similar process school by school to ensure they meet the unique demands of each campus. These day in the life scenarios can also be used to help provide families with a roadmap for what the experience of returning to learning will look like for them.

Chiefs for Change has made these materials and other planning tools available on our Schools and Covid-19 webpage under the section Support and Recommendations for Education Systems. In addition, our original 100-day reopening planning workbook supports the operational aspects of reopening and can be adapted to meet the needs of individual districts.

The foundations of our nation’s and our world’s economy have been dramatically changed by the COVID-19 outbreak, and that includes the foundation of how we deliver K-12 education. Since March, district by district, schools across America closed. Educators, students, and families were thrown into a new and evolving frontier of remote and digital learning without an instruction manual. There is not a single person among us – in education, business, or government – who has lived through a disruption of this magnitude. And as we begin a slow return to a very radically new normal, we cannot afford for this disruption to create a lost generation of students. Nor can we afford any solutions that further widen opportunity gaps between students with means and the most vulnerable kids in our systems.

Reopening schools will test our resolve. But done right – with proper planning and objective, iterative pressure testing – it can help us rebuild our education system to be more innovative and more responsive.

Dr. Julia Rafal-Baer is the chief operating officer of Chiefs for Change, a bipartisan network of state and district education chiefs. A former assistant commissioner at the New York State Education Department, Rafal-Baer earned a Ph.D. in education policy from the University of Cambridge, where she was a Marshall Scholar. She began her career as a special-education teacher in the Bronx.

Dr. Peter Gorman is Chief in Residence with Chiefs For Change, executive coach for superintendents and senior leadership teams, and the author of the book, “Leading a School District Requires Clarity, Context, and Candor: An Aligned System to Increase Student Achievement at Scale.” He is the former Superintendent of the Tustin Unified School District and Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools in Charlotte, North Carolina.