YONKERS, N.Y.—Brian Schulder, the security and safety director at Yonkers Public Schools, considers himself an educator, first and foremost. He’s not some hardened, former city beat cop or detective—he’s spent a majority of his 20-plus years in this large urban district teaching and coaching.

“I think being an educator lets me see things from a perspective that a career law enforcement-only person probably wouldn’t see when handling student-related cases,” says Schulder, a graduate of Yonkers’ Roosevelt High. “I look at everything possible before making a decision—transcripts, credits, is a student on track to graduate? We take the academic, social and mental approaches.”

He worked as a security guard at Yonkers Raceway to pay his way through multiple teaching credentials, which include master’s degrees in education administration and special education. While teaching during the day, he moved up the ranks to security management at night. He became the district’s security chief in 2016, overseeing 39 schools and 70 officers in the district, which borders New York City to the north.

“The role of the security director is making sure we have an emergency management plan that informs all the stakeholders, that is easy to follow and that students are fully aware of,” Yonkers Superintendent Edwin M. Quezada says. “It’s also critical to be sure we continue to have a superb relationship with the Yonkers Police Department, so concerns become a team problem rather than just a board of education problem.”

What are students concerned about?

The unpredictability of his job keeps him sharp, Schulder says. If he has a routine, it’s that he often spends the day speaking with educators, staff and young people in the district’s schools.

“You have to be in the schools every day, speaking with the students, to get an idea of what’s really going on,” he says. “They will tell you the truth, and they will tell you their concerns.”

He starts conversations casually, eventually probing into how secure students feel in their buildings. Many students consider themselves safe, he says, but school shootings around the country invariably heighten tensions. Today’s students are resilient, yet they also suffer heightened levels of anxiety. Schulder lays the blame on a single source: “When I went home when I was a student, I had neighborhood friends and activities, and I was shut off from everything else,” he says. “Our kids today are never shut off because of technology and social media.”

The negative side of the digital world adds extra pressure as students develop psychologically and physically. They also worry about neighborhood dangers. “One sentiment I hear is, ‘I know you can keep me safe, but I’m concerned about what happens when I leave school,’” he says. “That’s where you need the community and the police department involved.”

Partnering with the police

The potential for neighborhood conflicts to filter into schools is among the many reasons Schulder maintains a strong relationship with the Yonkers police, which, he says, “has never been better.”

“It has helped us stop things from happening,” he adds.

Constant communication with law enforcement allows administrators to lock down a building—and keep everything operating normally—if there’s trouble near a school. Schulder also conducts frequent tabletop exercises with firefighters and paramedics so all responders and school personnel know everyone’s role in an emergency.

Schulder brings the police department into the district to conduct extensive and realistic active shooter exercises with teachers and administrators. “That training is constantly updated, almost on a weekly or monthly basis,” he says. “After each unfortunate incident, law enforcement and administrators always look at what took place and try to learn something.”

Administrator training sessions have involved rubber bullets, which have distressed some participants, adds Quezada, the superintendent. “Some people have felt uncomfortable taking part, but it raises a level of awareness for them, particularly if they have never heard a gun being discharged,” he says.

Schulder also speaks weekly with Yonkers’ first deputy police chief and meets regularly with the department’s gang unit and youth division. They share intelligence about incidents that have occurred in schools and out in the city. “They let us know about things that have happened within Yonkers during the week, especially those that involve students or gangs,” he says. “I’ll take that information and pass it on to building principals.”

A human in a uniform

On the flip side, Schulder also wants to strengthen the student and police connection. The Cops & Kids program brings uniformed officers into elementary schools to chat with small groups of students for about 90 minutes. These are not “Officer Friendly” visits of old, in which officers simply admonish students about drug use and criminal behavior.

“We’ve taken that old model and thrown it in the garbage,” he says. Students will often ask officers very personal questions about their jobs, families and hobbies. And while the ethnic breakdown of the police force hasn’t quite caught up with the diversity of the district, Schulder sees the relationship improving. “The program takes the uniform and creates a human being,” he says. “It takes a child and gives the officer a different perspective as to whom they’re serving.”

However, Schulder knows that police presence and certain security tools, such as airport-style metal detectors, can make students uncomfortable. Yonkers security personnel only carry hand-held metal detectors and officers come in plainclothes and conceal their weapons when they visit for a meeting or a school security review. “When we create school to be very regimented, very institutionalized—and when you’re dealing with urban education systems—it can mirror what a prison looks like.”

Not enough tech dollars

The lack of metal detectors doesn’t mean the Yonkers security system is low-tech. Schulder is now integrating building surveillance with access control systems, which include ID card readers to unlock doors and keep a time-stamped log of visitors. He is also installing access control on all school doors, so security personnel can monitor everyone who comes and goes. Building administrators will also get alerts on their phones anytime a door is opened when it’s not supposed to be. These measures not only keep undesirables out, but they can prevent students from leaving school during class. The latter concern became a bigger priority in 2014 after a student with autism walked out of his school in nearby Queens and drowned in the East River.

Yonkers police officers also have complete access to the district’s surveillance cameras and building blueprints, which they can bring up in their patrol cars and precincts. State and federal grants have helped strengthen the district’s security system. But large urban districts still lack adequate funds, especially considering that installing a new security system in one building can cost a half-million dollars, Superintendent Quezada says.

“The dollars are not available,” he says.

Personal potential

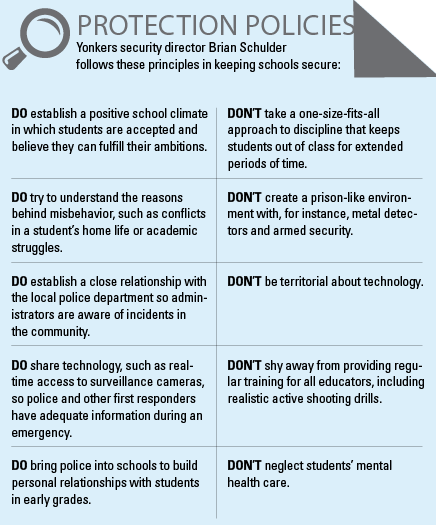

follows these principles in keeping schools secure

But even the latest technology can’t fully protect students or a school. Climate represents a major component of safety, Quezada adds.

The district has revamped its code of conduct to focus more on restorative disciplinary practices that de-emphasize punishments such as suspension, and focus on the cause of an outburst or scuffle. “Our first objective when dealing with a student’s transgression is finding out why they did what they did, and to try to get them back into the classroom as quickly as possible without having recidivist behavior,” Schulder says.

Students still risk suspension, expulsion or arrest for more serious offenses, such as bringing a weapon to school.

A climate where all ethnicities, lifestyles and religions are accepted—and where social-emotional development is supported—reduces the likelihood of someone becoming violent. Mental health care should become as high a priority as teaching math or English, Quezada adds.

“We cannot just arm every teacher or bring five police officers into every school,” he says. “The strategy has to be more counselors, more psychologists, more social workers.”